Table of Contents

I. Pierre Bourdieu: Early Life, Background, and Key Influences

1. Early Childhood and Family Background

2. Academic Beginnings and Initial Education

3. Key Influential Figures and Academic Streams

4. Philosophical and Academic Influences on Bourdieu

1) The Influence of Structuralism

2) Marxism and Social Reproduction Theory

3) The Impact of Phenomenology and Existentialism

II. Bourdieu’s Early Work: From Ethnography to Sociology

1. Early Studies: Agricultural Society and Culture

2. Bourdieu’s Ethnographic Approach

3. First Major Study: The Social Structure of Algerian Countryside

III. The Development of Bourdieu’s Social Theory

1. Emergence of Social Reproduction and Symbolic Violence Concepts

2. Bourdieu’s First Major Book: La Distinction

3. Development of Bourdieu’s Theories and Academic Career

IV. Cultural Capital: The Foundation of Bourdieu’s Sociology

1. Definition and Development of Cultural Capital

2. Types of Cultural Capital

3. A New Approach to Social Inequality

V. Habitus: The Internalization of Social Structures

1. Definition and Formation of Habitus

2. The Relationship Between Individual Behavior and Social Norms

3. The Influence of Habitus on Social Structure and Personal Actions

VI. The Theory of Social Fields: Competition and Power Dynamics

1. Development of the Concept of Social Fields

2. Types of Capital and Power Structures Within Fields

3. Competition Within Fields and the Role of Cultural Capital

VII. Symbolic Violence: Understanding Social Inequality

1. Definition of Symbolic Violence

2. The Role of Symbolic Violence in Power and Domination

3. Everyday Practices of Symbolic Violence

VIII. The Role of Education in Social Reproduction

1. The Theory of Social Reproduction Through Education

2. The Relationship Between Education and Class Reproduction

3. The Reproduction of Cultural Capital in Education

IX. Taste and Class: Aesthetic Preferences as Social Markers

1. The Relationship Between Aesthetic Taste and Social Class

2. The Connection Between Taste and Capital

3. The Role of Aesthetic Preferences in Symbolic Violence

X. Social Mobility: The Illusion of Equal Opportunity

1. Social Mobility and Its Constraints

2. The Discrepancy Between Equal Opportunity and Actual Mobility

3. The Limited Role of Class and Cultural Capital in Social Mobility

XI. Bourdieu’s Critique of Economic Capitalism

1. Critique of Economic Capitalism and Its Theoretical Contributions

2. The Interaction of Economic and Cultural Capital in a Capitalist Society

3. Bourdieu’s Critique in The Social Structures of the Economy

XII. The Media and the Reproduction of Cultural Capital

1. The Relationship Between Media and Cultural Capital

2. The Reproduction of Cultural Values Through the Media

3. Class and Cultural Distinctions in Media Representations

XIII. Bourdieu’s Influence on Contemporary Social Theory

1. Bourdieu’s Impact on Contemporary Social Theory

2. Modern Applications of Cultural Capital, Habitus, and Symbolic Violence

3. The Influence of Bourdieu’s Theories on Sociology and Anthropology

XIV. Critiques of Bourdieu: Limitations and Controversies

1. Major Critiques of Bourdieu’s Theories

2. Controversies Regarding Structuralist Determinism

3. The Limitations of Bourdieu’s Theories and Proposed Solutions

XV. Conclusion: The Lasting Legacy of Pierre Bourdieu’s Theory

1. The Modern Value and Ongoing Impact of Bourdieu’s Theories

2. Bourdieu’s Legacy in 21st-Century Social Sciences

3. Contemporary Applications and Social Practices of Bourdieu’s Theories

Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002)

I. Pierre Bourdieu: Early Life, Background, and Key Influences

1. Early Childhood and Family Background

Pierre Bourdieu was born on August 1, 1930, in the small town of Denguin, located in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques region of southwestern France. He came from a modest, working-class family, with his father being a farmer and his mother a housewife. Bourdieu’s early life was shaped by his rural upbringing, which gave him a unique perspective on social structures. His family’s financial constraints and his provincial upbringing would later influence his focus on class, education, and cultural capital.

Bourdieu’s upbringing provided him with a first-hand understanding of the stark contrasts between different social classes and the subtle mechanisms of social stratification. His experiences growing up in a small town shaped much of his later academic work, especially his examination of class divisions in French society.

2. Academic Beginnings and Initial Education

Bourdieu’s academic journey began in Paris, where he attended the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in 1951. His academic excellence led him to study philosophy under the mentorship of prominent intellectuals such as Louis Althusser, who would later influence Bourdieu’s Marxist leanings. Although Bourdieu initially trained as a philosopher, he was deeply influenced by the work of social theorists, which led him to shift his focus towards sociology.

During his early years at ENS, Bourdieu was exposed to the intellectual climate of post-war France, where existentialism, Marxism, and structuralism were the dominant schools of thought. This period of intellectual ferment shaped his theoretical orientation. His encounters with philosophers like Gaston Bachelard and the sociologist Emile Durkheim left a lasting impression on him. These encounters laid the groundwork for his later synthesis of various intellectual traditions in his own work.

3. Key Influential Figures and Academic Streams

Bourdieu’s ideas were shaped not only by his experiences and personal background but also by his interactions with key intellectual figures. His early work was influenced by the structuralist school of thought, especially the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss. Lévi-Strauss’ structural anthropology and the emphasis on social structures had a lasting impact on Bourdieu, who later extended these ideas into the realm of sociology.

Another major influence on Bourdieu was Karl Marx, whose analysis of class and power structures deeply informed Bourdieu’s approach to social theory. Bourdieu was particularly drawn to Marxist ideas of class struggle and the ways in which economic capital intersects with cultural and social power. His interest in Marxism, however, led him to critique the purely economic focus of traditional Marxist theory, prompting him to incorporate cultural elements into his understanding of class and power.

4. Philosophical and Academic Influences on Bourdieu

1) The Influence of Structuralism

Bourdieu was deeply influenced by structuralism, particularly the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, who examined human culture through the lens of deep structures and binary oppositions. This influence can be seen in Bourdieu’s adoption of a structural approach to understanding society, though Bourdieu diverged by emphasizing the role of agents and social practice.

2) Marxism and Social Reproduction Theory

Bourdieu incorporated Marxist ideas, especially the concept of social reproduction, into his own work. Marx’s focus on economic class divisions and power dynamics influenced Bourdieu’s theories of cultural capital and social mobility. However, Bourdieu expanded Marxist theory by examining how cultural forms, such as education, also contribute to the reproduction of social inequality. His seminal work on social reproduction and class distinctions later culminated in his major book, La Distinction (1979).

3) The Impact of Phenomenology and Existentialism

Bourdieu was influenced by phenomenology, particularly the work of Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Phenomenology’s focus on embodied experience and lived reality led Bourdieu to develop the concept of habitus, which describes how social structures are internalized in individuals through their daily practices and embodied experiences. This concept was later foundational in his sociological framework.

II. Bourdieu’s Early Work: From Ethnography to Sociology

1. Early Studies: Agricultural Society and Culture

Bourdieu’s early academic career was largely shaped by his ethnographic work in Algeria during the late 1950s. At the time, Algeria was a French colony, and Bourdieu conducted research on the rural Kabyle community, which provided him with a deep understanding of how social structures are maintained and reproduced in a traditional, rural society. This work led to his first major sociological study, The Algerian Revolution (1965), which explored the intersection of colonialism, social class, and cultural practices.

Bourdieu’s ethnographic fieldwork in Algeria focused on understanding the local social structures, especially how power and class were embedded in cultural practices. His fieldwork not only provided the foundation for his understanding of social hierarchies and inequality, but it also introduced him to the importance of culture in shaping people’s experiences of class and social identity.

2. Bourdieu’s Ethnographic Approach

Bourdieu’s approach to ethnography was distinct from that of traditional anthropologists. He rejected the idea of ethnography as merely an observational tool, instead emphasizing that researchers should also examine their own role in shaping social knowledge. He introduced the concept of “reflexivity,” stressing the importance of recognizing the researcher’s position and biases within the research process. This would later inform his critique of objectivity in traditional social science.

In his ethnographic studies, Bourdieu also introduced the concept of “habitus,” which refers to the ingrained habits, dispositions, and practices that individuals develop in response to their social environments. This concept would become central to his later work, linking individual agency to the broader social structures of class and power.

3. First Major Study: The Social Structure of Algerian Countryside

Bourdieu’s first major academic project was his study of the rural Kabyle society in Algeria. Through his research, he revealed how local social structures, such as kinship and land ownership, played a critical role in maintaining social hierarchies. His study of Kabyle society, published in his book Sociology of Algeria (1964), illustrated how social reproduction works at the cultural level. He demonstrated how cultural capital such as language, customs, and practices was transmitted across generations, reinforcing social stratification and inequality.

The work in Algeria also contributed to Bourdieu’s critique of colonialism, as he examined how colonial power dynamics disrupted local traditions and social structures, but simultaneously helped in creating new forms of inequality. Through this research, Bourdieu was able to integrate the political dimension of social theory into his broader sociological framework.

III. The Development of Bourdieu’s Social Theory

1. Emergence of Social Reproduction and Symbolic Violence Concepts

Bourdieu’s social theory developed significantly over the course of his career, with key concepts such as reproduction sociale (social reproduction) and violence symbolique (symbolic violence) emerging as central to his work. Social reproduction refers to the ways in which social inequalities, particularly those related to class, are perpetuated across generations. Bourdieu argued that social structures such as family, education, and media play a role in reproducing the social order by transmitting capital culturel (cultural capital) and shaping individuals’ dispositions (dispositions).

Social reproduction can be understood through an example from education. For instance, a student from an upper-class family is likely to be exposed to cultural activities such as museum visits or private tutoring, which can enhance their capital culturel. Conversely, a student from a working class family may not have access to such resources, leading to a disparity in educational achievement. This unequal access to capital culturel contributes to the reproduction of class divisions.

Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence is also key to understanding social inequality. Violence symbolique refers to the subtle ways in which power is exercised through culture and social norms, often without the individuals involved being fully aware of it. For example, the expectation that students adopt certain behaviors or ways of thinking in schools can be seen as a form of symbolic violence particularly when students from lower social classes feel alienated by educational institutions that are structured around middle class norms.

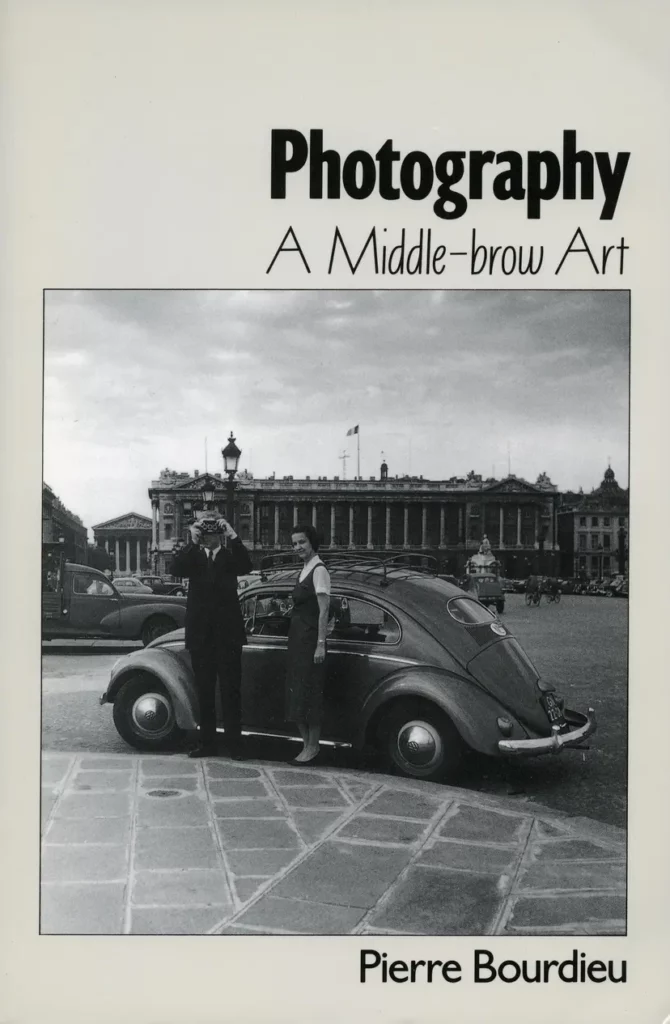

2. Bourdieu’s First Major Book: La Distinction

Bourdieu’s first major sociological work, La Distinction (1979), is one of the most important texts in understanding his theories of class and capital culturel. In this book, Bourdieu examined the relationship between cultural tastes (such as preferences for art, music, and food) and social class. He argued that people’s tastes are not just individual preferences but are deeply influenced by their social position and the capital culturel they have access to. In essence, taste becomes a marker of class distinction.

For example, an individual from a wealthy background might prefer classical music, fine wine, or gourmet food, whereas someone from a working-class background might prefer pop music, fast food, or beer. These tastes are not arbitrary; they reflect the individual’s access to capital culturel and their social standing. According to Bourdieu, these preferences are part of a broader social system that uses capital culturel as a tool for maintaining social hierarchies.

In La Distinction, Bourdieu also introduced the idea of the “aesthetic disposition” (disposition esthétique), which refers to the ability to appreciate certain forms of culture in ways that are aligned with one’s social position. This disposition is learned through exposure to cultural practices that are valued by the dominant classes.

3. Development of Bourdieu’s Theories and Academic Career

Throughout his academic career, Bourdieu developed a comprehensive sociological framework that integrated key concepts such as capital culturel, champs sociaux (social fields), and habitus (habitus). His theories sought to explain not just how social structures function, but how they are maintained and reproduced through everyday practices and cultural mechanisms.

Bourdieu’s work on social fields (champs sociaux) is central to his theory. Champs sociaux refer to areas of social life such as education, art, politics, or the economy where individuals and groups compete for various forms of capital. Within each champ, there are distinct rules, power structures, and forms of capital that individuals must navigate to achieve success. For instance, in the field of education, academic qualifications and cultural knowledge can be seen as the forms of capital that influence individuals’ opportunities for upward mobility.

Through his research and publications, Bourdieu expanded the scope of sociological inquiry by exploring the intersection of culture, power, and social structures. His interdisciplinary approach made his work influential across fields such as sociology, anthropology, and cultural studies.

IV. Cultural Capital: The Foundation of Bourdieu’s Sociology

1. Definition and Development of Cultural Capital

Cultural capital, a concept introduced by Pierre Bourdieu, refers to non-economic resources that individuals can leverage to gain social advantages. Unlike economic capital, which is based on material wealth, cultural capital includes intangible assets such as knowledge, skills, education, and cultural tastes. These resources are accumulated over time and allow individuals to access higher social positions and distinguish themselves from others in society.

Cultural capital is integral to Bourdieu’s broader theory of social stratification. It is tied to the way individuals are socialized, how they interact with the world, and how they assert their identities. Cultural capital plays a key role in the reproduction of social inequalities by enabling individuals to use their cultural competencies to navigate and succeed in various social and professional spheres. People with greater cultural capital tend to have better opportunities for upward mobility, better access to resources, and are more likely to achieve higher social status.

Bourdieu identified three forms of cultural capital: embodied, objectified, and institutionalized. These forms reflect the different ways in which cultural capital is acquired, expressed, and recognized by society. They offer a framework for understanding how cultural capital functions in different contexts, from personal behavior and education to professional success.

2. Types of Cultural Capital

Bourdieu’s framework of cultural capital is divided into three primary types: embodied, objectified, and institutionalized cultural capital. Each type captures a different aspect of how cultural resources are accumulated and deployed by individuals within social contexts.

• Embodied Cultural Capital (incorporé): This type of cultural capital refers to the knowledge, skills, and competencies that individuals internalize through socialization, education, and life experiences. It is the personal cultural competence embedded within an individual, which influences their behavior, speech, tastes, and interaction with others. Embodied cultural capital includes things such as language fluency, manners, intellectual knowledge, and the ability to navigate various social and cultural environments. It is formed over time and is difficult to measure because it exists within an individual’s body and mind.

• Objectified Cultural Capital (objectivé): Objectified cultural capital refers to physical objects that hold cultural significance, such as books, works of art, musical instruments, or luxury goods. These objects are symbols of cultural wealth and status, often used as markers of distinction between social classes. The possession of these cultural objects signals an individual’s access to cultural resources, which in turn influences their social position. Objectified cultural capital is visible and can be shared, exchanged, or displayed, making it an important tool for reinforcing social identity.

• Institutionalized Cultural Capital (institutionnalisé): This form of cultural capital involves the recognition of an individual’s cultural assets by societal institutions, such as educational degrees, professional qualifications, and certifications. Institutionalized cultural capital plays a crucial role in formal settings like education and the workplace, where individuals gain access to specific opportunities and social positions based on their recognized qualifications. It acts as a form of validation that grants legitimacy to an individual’s cultural competence and serves as a key mechanism for social mobility and differentiation.

For example, someone with a university degree in law possesses institutionalized cultural capital that allows them to enter the legal profession. Without such a degree, that same individual would not have access to the same opportunities in the legal field. Similarly, someone who has been raised in a culturally enriched environment, with exposure to intellectual discussions and fine art, would accumulate embodied cultural capital that might give them an advantage in highbrow cultural contexts. The combination of embodied, objectified, and institutionalized cultural capital helps to explain why social inequalities persist, as individuals with more access to these forms of cultural capital are better positioned in society.

3. A New Approach to Social Inequality

Bourdieu’s concept of capital culturel provides a new way of understanding social inequality. Rather than focusing solely on economic disparities, Bourdieu showed how cultural factors also contribute to the persistence of social hierarchies. Capital culturel can be inherited from family, acquired through education, or accumulated through personal experiences. This accumulation process helps to explain how class divisions are maintained across generations.

Capital culturel can also be converted into capital économique (economic capital), which allows individuals to access better jobs or higher social status. For example, a person with a high level of capital culturel in the form of education and refined tastes might be more likely to secure a prestigious job, thus translating their capital culturel into economic success.

By analyzing the ways in which capital culturel operates in various social fields, Bourdieu provided a powerful tool for understanding how social inequalities are reproduced over time. Capital culturel, along with other forms of capital such as capital économique and capital social (social capital), shapes individuals’ opportunities, behaviors, and social mobility.

V. Habitus and Social Fields: The Mechanisms of Social Action

1. Definition and Formation of Habitus

One of Bourdieu’s most important concepts is habitus (habitus). Habitus refers to the internalized dispositions, habits, and ways of thinking that individuals acquire through their life experiences. These dispositions are shaped by an individual’s social background, family upbringing, education, and other experiences. Habitus plays a key role in shaping how individuals perceive the world, how they act in social situations, and how they respond to the structures around them.

For example, a person raised in a family that values education might develop a habitus that makes them more likely to pursue higher education. On the other hand, someone from a family where education is not emphasized might develop a different habitus, one that is less focused on academic achievement. Habitus is thus a product of one’s social environment and is reflected in everyday practices and behaviors.

Bourdieu also argued that habitus is not only shaped by an individual’s immediate social context but also interacts with broader social structures. In this sense, habitus is both the product and the producer of social structures, creating a cyclical relationship between individuals and society.

2. The Relationship Between Individual Behavior and Social Norms

Habitus explains the relationship between individual behavior and societal norms. It suggests that individuals naturally internalize the social norms and values of the environment they grow up in. These norms are not imposed externally but become part of the individual’s habits, tastes, values, and ways of thinking, which in turn shape their behavior.

According to Bourdieu, these norms are not only external forces but become deeply embedded in individuals’ ways of perceiving and acting in the world. Habitus shapes individuals’ actions in a way that aligns with the broader social structure they are part of. For example, people from different social classes have distinct behaviors, preferences, and lifestyles, influenced by the specific habitus they have internalized. Through this process, social structures are reproduced across generations, without people necessarily being consciously aware of it.

3. The Influence of Habitus on Social Structure and Personal Actions

Habitus plays a crucial role in both reproducing and reinforcing the social structure and influencing individual actions. While individuals act in ways that align with their internalized habitus, their behaviors also contribute to the ongoing reproduction of the social structure. Bourdieu describes this as the “reproduction of practice”, where individuals’ daily actions continuously reproduce the social norms, hierarchies, and power relations embedded in society.

For example, children from higher social classes are often taught values that emphasize education, cultural capital, and certain tastes, which helps them maintain their social status as adults. On the other hand, individuals from lower social classes develop a different habitus, shaped by their environments, and this often results in distinct life paths and social practices.

Habitus is a mechanism that not only shapes individual behavior but also ensures the continuity of social structures. It helps explain why social inequalities persist over time, as the practices and dispositions that maintain these structures are passed down through generations, often unconsciously. In this way, habitus functions as a bridge between individual actions and the broader social forces that shape those actions.

VI. The Theory of Social Fields: Competition and Power Dynamics

1. Development of the Concept of Social Fields

The concept of social fields (champs sociaux) is central to Bourdieu’s theory, referring to structured social spaces in which individuals and groups engage in competition for various forms of capital (capital). A social field is not merely a collection of individuals; rather, it is a dynamic arena where power struggles occur and where actors contest resources that are valued by that particular field.

Bourdieu’s notion of a social field goes beyond the individual to focus on the interactions within these fields, which can be economic, cultural, educational, or political. For example, the academic field (champ académique) is an arena where scholars compete for recognition, resources, and authority in the form of academic titles, funding, or publication prestige. Fields are thus sites of power (pouvoir) and competition (compétition), where the distribution and exchange of capital influence individuals’ success and status.

Social fields evolve over time, often being shaped by the broader social structure, and they can interact with one another. For instance, the economic field (champ économique) may influence the political field (champ politique), and vice versa. These interactions define the power dynamics and relationships within and between fields, determining the access to and control over valuable resources.

2. Types of Capital and Power Structures Within Fields

Bourdieu identified different types of capital (capital) within each field that play a critical role in power dynamics. These types of capital include economic capital (capital économique), cultural capital (capital culturel), social capital (capital social), and symbolic capital (capital symbolique). Each field values different forms of capital, and individuals or groups strive to accumulate the capital that is most valuable within a given field.

• Economic capital (capital économique) refers to material resources, such as money or property, which are critical in fields like business or economics.

• Cultural capital (capital culturel), which includes knowledge, education, and taste, is especially valuable in fields like academia, art, and culture.

• Social capital (capital social) relates to the networks and relationships that individuals can leverage within fields like politics or business.

• Symbolic capital (capital symbolique) is the prestige, honor, or recognition an individual gains, often in the form of titles, awards, or status, which can be a key element in fields like education or media.

The power dynamics within a field are often determined by the distribution and exchange of these forms of capital. Those who control or accumulate the dominant form of capital in a field are able to assert power over others, influencing decisions and establishing their dominance within the field.

3. Competition Within Fields and the Role of Cultural Capital

Competition within fields (compétition dans les champs) occurs as individuals or groups compete for dominance and access to the most valued resources or capital in that field. The role of cultural capital (rôle du capital culturel) becomes especially significant in fields like education, art, or academia, where knowledge, taste, and cultural credentials are highly prized.

For example, in the educational field, students with high cultural capital, such as those from well-educated families with access to cultural resources (e.g., books, art, travel), are better positioned to succeed academically. This advantage, however, is often invisible or unacknowledged, as the education system tends to favor students who have acquired specific cultural competencies, reinforcing existing social inequalities.

In cultural fields, the competition is not only about monetary wealth or material success but also about symbolic power (pouvoir symbolique). Those who can define what is culturally legitimate (légitime culturellement) and who possess the cultural distinctions (distinctions culturelles) that are recognized as valuable within the field wield power. For instance, artists, scholars, and critics who control cultural norms and preferences shape the discourse within a cultural field, influencing which works of art, ideas, or practices are considered valuable.

The competition in these fields often centers around the transformation of cultural capital (transformation du capital culturel) into symbolic capital (capital symbolique), where individuals gain prestige or recognition based on their cultural knowledge or artistic contributions. This dynamic highlights how the exchange and accumulation of cultural capital contribute to the broader social stratification that Bourdieu sought to explain.

VII. Symbolic Power: Symbolic Violence: Understanding Social Inequality

1. Definition of Symbolic Violence

Symbolic violence (violence symbolique) is one of Pierre Bourdieu’s most significant concepts, referring to the subtle, often invisible forms of violence that exist within social structures. Unlike physical violence, symbolic violence is not overt or explicit but instead manifests in the way social norms, values, and expectations are internalized and accepted by individuals, often without question. It operates through language, culture, and everyday practices, reinforcing social hierarchies and inequalities.

Symbolic violence occurs when dominant groups impose their cultural norms and values upon subordinate groups in a way that is perceived as legitimate and natural. This form of violence is “symbolic” because it involves the exercise of power through the creation and dissemination of meanings and symbols. The victim of symbolic violence may not even recognize their subjugation, as the imposed social structures are internalized and normalized over time.

For example, the concept of beauty in society is often shaped by dominant cultural norms. When individuals fail to meet these standards whether in terms of appearance, behavior, or taste they may experience symbolic violence. The judgments passed on them as “ugly” or “improper” become internalized, leading to feelings of inadequacy, shame, and self-rejection. This reinforces social inequality, as those who do not conform to the “ideal” are marginalized and excluded.

2. The Role of Symbolic Violence in Power and Domination

Symbolic violence plays a crucial role in maintaining power (pouvoir) and domination (domination) within society. By shaping individuals’ perceptions of reality, symbolic violence perpetuates existing social structures and reinforces the status quo. It is not the result of force or coercion but rather the power of persuasion, where individuals come to accept the social hierarchy as natural, inevitable, or even just.

In this sense, symbolic violence is closely tied to the mechanisms of social reproduction (reproduction sociale). Through the family, education system, media, and other social institutions, dominant groups reinforce their norms and values, ensuring that their power is passed on to future generations. This process of socialization makes inequalities seem justified and normal, contributing to the continuity of social structures.

For example, the ways in which gender roles are reinforced through media and education can be understood as a form of symbolic violence. By presenting certain behaviors, qualities, or roles as appropriate for one gender but not the other, individuals internalize these expectations and, in turn, reproduce gender inequality. Those who deviate from these roles are often subjected to symbolic violence, as their actions or identities are framed as “abnormal” or “illegitimate.”

Symbolic violence allows the dominant groups to assert their power without the need for direct conflict or force. It is a form of soft power (pouvoir doux) that is, in many ways, more effective because it works at the level of perception and belief.

3. Everyday Practices of Symbolic Violence

Everyday practices of symbolic violence (pratiques quotidiennes de violence symbolique) refer to the subtle, routine ways in which symbolic violence is enacted in daily life. These practices can be seen in the norms (normes) and behaviors (comportements) that govern how individuals act, interact, and are perceived by others. It often occurs in the form of social judgments, stereotypes, or biases that are reinforced through day-to-day interactions.

For example, consider how individuals are judged based on their accent (accent), clothing (vêtements), or social background (origine sociale). These judgments are often made unconsciously, yet they have profound implications for an individual’s opportunities and social standing. Someone from a lower social class or with a non-standard accent may be seen as less competent or less worthy of respect, even if these judgments are never explicitly stated. The individual is not physically harmed, but their position in the social hierarchy is reinforced, and they may internalize these negative perceptions.

Similarly, symbolic violence is evident in educational practices (pratiques éducatives), where certain forms of knowledge, language, or behavior are seen as more valuable than others. For example, a child who is raised in an environment where academic success is prioritized and who speaks a “prestigious” dialect may fare better in the education system than a child from a working-class background, who may speak a regional dialect or lack access to certain cultural resources. This disparity is not due to overt discrimination but to the invisible imposition of dominant cultural norms that devalue certain forms of knowledge or expression.

The role of symbolic violence is most visible in situations where individuals internalize the dominant culture’s standards, even when those standards work against their own interests. For instance, in the context of the workplace, a person who adopts the values and attitudes of a more privileged group may be more likely to succeed, while someone who holds different values or exhibits behaviors outside of the norm may be subtly pushed aside. The former experiences symbolic violence through their conformity, while the latter suffers symbolic violence through exclusion or marginalization.

In everyday life, these practices reinforce the boundaries between different social groups, perpetuating inequality and preserving the status quo. Because symbolic violence operates invisibly and often goes unrecognized, it is one of the most insidious forms of social control and a key mechanism for maintaining social hierarchy (hiérarchie sociale) and class distinctions (distinctions de classe).

VIII. The Role of Education in Social Reproduction

1. The Theory of Social Reproduction Through Education

Social reproduction (reproduction sociale) refers to the process by which social structures and inequalities are maintained and passed down from one generation to the next. Pierre Bourdieu argued that education plays a central role in this process, as it is one of the key institutions through which cultural, social, and economic inequalities are transmitted. Education is not merely about the transfer of knowledge but also a means of reinforcing social hierarchies.

Bourdieu’s theory of social reproduction suggests that the education system is a key mechanism through which dominant cultural values (valeurs culturelles dominantes) are transmitted and normalized. The school system, through its curricula, teaching methods, and evaluation processes, tends to privilege the knowledge, values, and behaviors of the upper classes while devaluing the experiences and knowledge of lower-class students. This results in a process where children from wealthier families are better equipped to succeed in educational settings, as they have access to the cultural capital (cultural capital) that the education system values.

Bourdieu referred to the concept of cultural capital (capital culturel) as the social assets—such as education, tastes, knowledge, and skills that individuals accumulate through their upbringing, schooling, and experiences. Children from higher social classes often possess more cultural capital, which makes them more likely to succeed in educational environments. In contrast, children from working class or lower-income families often lack the same resources and cultural capital, making it harder for them to succeed.

In this way, education does not simply function as a leveler of opportunity, but instead reproduces social inequality by reinforcing the cultural and social advantages of dominant groups while marginalizing those from lower-class backgrounds.

2. The Relationship Between Education and Class Reproduction

Bourdieu’s theory emphasizes the relationship between education (éducation) and class reproduction (reproduction de classe). Education, according to Bourdieu, does not offer equal opportunities to all students but rather plays a role in the reproduction of existing class structures. Children from affluent families, who are socialized into the dominant class culture (culture dominante), are better prepared to succeed in the education system. They possess a higher level of cultural capital, which gives them an advantage in school settings.

In contrast, children from working-class or marginalized backgrounds often enter the education system with less cultural capital. Their tastes, behaviors, and knowledge are less aligned with the cultural norms and expectations of the education system. As a result, they are less likely to perform well academically, which limits their future opportunities and reinforces the class divide. This process is often subtle and unconscious, as the education system itself is perceived as neutral, even though it systematically favors the upper classes.

Bourdieu’s work shows that educational institutions are not neutral spaces where individuals are judged purely on their abilities and talents. Rather, they are places where the existing social order is reproduced. The education system reflects and reinforces the social hierarchies that exist in society, ensuring that those with higher social capital are able to accumulate more educational success, while those from lower social backgrounds are at a disadvantage.

3. The Reproduction of Cultural Capital in Education

Cultural capital (capital culturel) is a key concept in Bourdieu’s theory of education. It refers to the non-financial social assets that individuals acquire over time, such as knowledge, tastes, manners, language, and intellectual skills, which are often valued in the education system. Schools tend to value certain types of cultural capital those that align with the dominant or elite culture while ignoring or devaluing other forms of knowledge and experience.

In the education system, children from higher social classes are typically raised with the types of cultural capital that align with what is valued in schools. For example, they are more likely to come from families that read books, engage in intellectual discussions, or travel, all of which contribute to a broader range of knowledge and skills. This makes it easier for them to succeed academically, as they are already equipped with the cultural tools that schools reward.

In contrast, children from lower-class families may not have the same exposure to cultural capital that schools prioritize. As a result, these students may struggle in the classroom, as they lack the linguistic skills, references, or cultural knowledge that is favored in educational settings. This difference in cultural capital can result in lower academic achievement and fewer opportunities for social mobility.

Through the education system, the dominant cultural capital is reproduced (reproduit) in each generation, reinforcing the social structure and ensuring that the privileges of the upper classes are passed down. In this way, education serves as a mechanism for the transmission of cultural capital, perpetuating the social advantages of dominant groups while hindering the upward mobility of those from lower social backgrounds.

Bourdieu’s analysis highlights how education is not simply a space for intellectual growth, but rather an institution that plays a crucial role in maintaining social inequality by reproducing the cultural capital of the elite and marginalizing those without access to it.

IX. Taste and Class: Aesthetic Preferences as Social Markers

1. The Relationship Between Aesthetic Taste and Social Class

In his theory, Pierre Bourdieu explored how aesthetic taste (goût esthétique) is deeply intertwined with social class and how individuals’ preferences for cultural products such as art, music, fashion, food, and literature—act as markers of social position. Bourdieu argued that taste is not a matter of personal choice or individual preference, but rather a reflection of one’s social position (position sociale) within the broader social structure.

For Bourdieu, taste is not just a simple aesthetic judgment, but a social indicator that helps to distinguish between the different social classes. He posited that people from higher social classes are more likely to have “refined” tastes that align with the cultural norms and values of the dominant class. In contrast, those from lower social classes may have tastes that align with more popular or working-class cultural forms, which are often devalued by society.

Bourdieu’s concept of distinction (distinction) is central here, as it refers to the process by which individuals within a society assert their social status through their aesthetic preferences. He argued that the tastes and preferences of the dominant classes are considered “legitimate,” while the tastes of subordinate groups are marginalized or seen as inferior. This hierarchical view of taste reinforces social boundaries and helps to maintain social inequality.

Taste is therefore not just about personal enjoyment but also about the social signaling (signalisation sociale) of one’s class position. For example, enjoying highbrow cultural products such as opera, classical music, or fine wine may signal membership in an elite social class, while preferring mass-produced pop culture or fast food may signal a lower-class position.

2. The Connection Between Taste and Capital

Bourdieu connected the concept of taste (goût) directly to capital, particularly cultural capital (capital culturel). He argued that an individual’s taste is shaped by the cultural capital they possess, which is accumulated through family background, education, and social experiences. People with higher levels of cultural capital tend to have tastes that align with the dominant cultural norms, while those with less cultural capital are more likely to have tastes that align with the popular or mass culture.

Cultural capital, as Bourdieu defined it, consists of knowledge, skills, education, and other forms of cultural proficiency that can be used to navigate the social world. Those with more cultural capital are better equipped to appreciate and engage with “legitimate” cultural forms such as classical art, sophisticated cuisine, or complex intellectual works because these forms align with the norms and values of the dominant social class. This gives them a social advantage in contexts such as the educational system or the professional world.

In contrast, those with less cultural capital may be drawn to more popular cultural forms, which are seen as less refined or less prestigious. This difference in taste reflects the ways in which social class affects access to cultural knowledge and the ability to engage with high status cultural forms. For Bourdieu, the connection between taste and capital reinforces social hierarchies and contributes to the reproduction of class distinctions.

By understanding taste as a form of capital, Bourdieu revealed how aesthetic preferences are not neutral but are used as tools for social differentiation. The preferences for certain cultural products or practices serve as a way of signaling one’s social position and reaffirming the boundaries between different social classes.

3. The Role of Aesthetic Preferences in Symbolic Violence

Bourdieu argued that aesthetic preferences (préférences esthétiques) play a crucial role in the perpetuation of symbolic violence (violence symbolique), which refers to the subtle, often invisible ways in which power and domination are exercised in society. Symbolic violence occurs when the cultural norms and values of the dominant group are imposed on other groups, often without their awareness. This creates a situation where certain forms of culture those valued by the dominant class—are treated as superior, while other forms are marginalized and devalued.

Through their aesthetic preferences, individuals from dominant social classes contribute to the process of symbolic violence by legitimizing (légitimer) certain cultural forms and disqualifying (disqualifier) others. For example, the preference for highbrow art over popular entertainment or the devaluation of working-class tastes can contribute to the social marginalization of those who do not conform to the dominant cultural standards.

Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence is particularly evident in the way that tastes are linked to social hierarchies. The dominant class uses its tastes to maintain its position of power, reinforcing its cultural superiority. By asserting that certain cultural forms are inherently more valuable or refined, the dominant group imposes its values on others, who are often unaware of the ways in which they are being subjected to this form of social domination.

In this sense, aesthetic preferences become a tool for social control. The tastes and preferences of the dominant class are often viewed as universal and objective, while the tastes of subordinated groups are viewed as inferior or less cultured. This process of social distinction (distinction sociale) through aesthetic preferences contributes to the reproduction of inequality by maintaining the cultural authority of the dominant groups.

Symbolic violence in the realm of taste works to naturalize (naturaliser) social inequalities, making them appear as if they are the result of inherent differences in cultural value rather than the product of power dynamics and social structures. This helps to maintain the status quo by obscuring the mechanisms through which social hierarchies are perpetuated and making it more difficult for subordinated groups to challenge the cultural dominance of the elites.

X. Social Mobility: The Illusion of Equal Opportunity

1. Social Mobility and Its Constraints

Pierre Bourdieu’s analysis of social mobility (mobilité sociale) emphasizes the constraints that prevent genuine movement between social classes, even in societies that claim to offer equal opportunities. Bourdieu argued that social mobility is often more limited than it appears, as it is shaped by the structure of social fields, the distribution of capital (capital), and the internalized dispositions of individuals (habitus).

Social mobility refers to the ability of individuals or groups to move up or down the social hierarchy, often through changes in education, occupation, or income. While many societies, especially in the West, promote the idea that anyone can succeed through hard work and talent, Bourdieu noted that structural barriers (barrières structurelles) such as unequal access to educational and economic resources make true mobility difficult for many individuals, especially those from lower social classes.

These constraints are not just economic, but also cultural. The distribution of cultural capital, such as education, social connections, and cultural knowledge, is not equal across all classes. People born into privileged families are more likely to inherit cultural capital that facilitates their success, while those from disadvantaged backgrounds may struggle to access the same resources, even if they work hard or possess talent.

Bourdieu’s concept of reproduction (reproduction) plays a key role here. He suggested that the educational system, media, and other institutions serve to reproduce the existing class structure by privileging those who already possess cultural capital, which limits the potential for upward social mobility.

2. The Discrepancy Between Equal Opportunity and Actual Mobility

Bourdieu’s critique of social mobility centers around the illusion of equal opportunity (illusion d’égalité des chances). While many societies claim that everyone has the same chance to succeed, Bourdieu argued that the reality is different, as individuals from different social classes are not starting from the same point. The social system is rigged in favor of those with greater cultural, economic, and social capital, which makes it much harder for individuals from lower social classes to move up.

Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic capital (capital symbolique) helps explain this discrepancy. Symbolic capital, which includes respect, prestige, and recognition, is often linked to the accumulation of cultural and economic capital. Those born into elite families are more likely to have access to symbolic capital, which in turn opens doors in education, employment, and social life. In contrast, individuals from less privileged backgrounds often struggle to accumulate the same capital, making it harder for them to move upward.

The educational system (système éducatif) is particularly important in this context. While it is often portrayed as a meritocratic institution that rewards effort and talent, Bourdieu argued that it disproportionately favors those who are already culturally aligned with the dominant social class. For example, children from wealthy families are more likely to attend prestigious schools and universities, where they are exposed to the cultural practices and social networks that facilitate social mobility. On the other hand, children from working class backgrounds may not have access to the same educational opportunities, even if they are equally talented.

As a result, the gap between the promise of equal opportunity and the reality of social mobility is wide. The barriers to upward mobility are deeply entrenched, and they are sustained by the unequal distribution of capital across social fields.

3. The Limited Role of Class and Cultural Capital in Social Mobility

While Bourdieu acknowledged that social mobility is possible to some extent, he argued that it is often limited (limité) by the constraints of class and cultural capital. The idea that individuals can rise above their social class through effort and talent is, in Bourdieu’s view, a myth (mythe), because it overlooks the structural advantages that come with being born into a higher social class.

Bourdieu’s habitus (habitus) plays a central role in this. Habitus refers to the deeply ingrained dispositions and ways of thinking that individuals develop based on their social position. These dispositions shape how people approach education, work, and life in general. For example, people from privileged backgrounds may have a habitus that aligns with the cultural expectations of the educational system and the labor market, giving them an advantage in terms of access to opportunities. In contrast, individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds may have a habitus that is more in line with working class norms, which can hinder their ability to navigate systems that favor the cultural practices of the elite.

Bourdieu also emphasized the role of economic capital (capital économique) in social mobility. While cultural capital plays a significant role, individuals with more economic resources have an easier time accessing opportunities that can lead to upward mobility, such as private education, travel, and social networking. As a result, economic capital remains one of the most significant factors in determining an individual’s chances for mobility, regardless of their cultural capital.

The role of cultural capital is not entirely negated, however. Bourdieu recognized that it can play a role in social mobility, particularly when individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds are able to acquire cultural capital that allows them to compete in more elite spheres. However, even with cultural capital, individuals must still overcome the deep seated inequalities in society, which often makes true social mobility more difficult than it appears on the surface.

In conclusion, Bourdieu’s analysis of social mobility reveals the complex ways in which class and capital shape individuals’ chances of moving up the social ladder. While opportunities for upward mobility may exist, the barriers created by unequal access to capital especially cultural and economic capital—make true social mobility much more limited than the ideal of equal opportunity suggests.

XI. Bourdieu’s Critique of Economic Capitalism

1. Critique of Economic Capitalism and Its Theoretical Contributions

Pierre Bourdieu’s critique of economic capitalism (capitalisme économique) focuses on the ways in which capitalism consolidates power, perpetuates inequalities, and structures social relations. While many sociologists and economists have focused on the purely economic aspects of capitalism, Bourdieu extended his analysis to the symbolic and cultural dimensions, which he believed are equally significant in understanding how capitalism operates.

Bourdieu argued that economic capitalism does not merely function as a market system based on supply and demand, but also as a social order (ordre social) that shapes people’s beliefs, behaviors, and interactions. In this system, economic capital (wealth, property, resources) is just one form of capital. However, it is often considered the most important and determinant form of power. The accumulation of economic capital, through inheritance, work, or investment, is crucial to social status, but Bourdieu contended that economic capital cannot fully explain social inequality without considering the symbolic power (pouvoir symbolique) and social capital (capital social) embedded in capitalist structures.

Bourdieu’s theoretical contribution to the critique of economic capitalism lies in his identification of the role of cultural capital (capital culturel) and symbolic violence (violence symbolique) in perpetuating social hierarchies. While classical Marxist theory emphasized the dominance of economic forces, Bourdieu emphasized that cultural practices, tastes, and educational attainments also function as forms of capital that legitimize the unequal distribution of economic power.

Thus, Bourdieu’s work goes beyond the analysis of economic transactions and profit accumulation. He argued that economic capitalism is not simply an economic system, but a socially constructed (socialement construit) system that operates through a complex network of cultural, social, and economic capitals that reproduce social inequalities.

2. The Interaction of Economic and Cultural Capital in a Capitalist Society

In Bourdieu’s view, economic and cultural capital are deeply intertwined and mutually reinforcing within capitalist societies. Economic capital refers to material resources such as money, property, or assets, while cultural capital encompasses knowledge, education, taste, and prestige. According to Bourdieu, economic capital and cultural capital cannot be understood separately; instead, they interact in ways that reinforce social stratification.

Bourdieu proposed that economic capital provides individuals with the material means to acquire cultural capital, such as education, cultural practices, and social connections. For instance, families with higher economic resources can afford better education for their children, access cultural institutions, and provide opportunities for social mobility (mobilité sociale). This acquisition of cultural capital helps maintain their social status across generations.

At the same time, cultural capital plays a key role in accumulating or preserving economic capital. Education, for example, allows individuals to acquire skills, knowledge, and qualifications that increase their potential for higher-paying jobs and greater economic success. However, Bourdieu emphasized that cultural capital is not equally distributed. Those from privileged backgrounds have greater access to cultural resources, making it easier for them to accumulate both economic and cultural capital, thus perpetuating the cycle of inequality.

The interaction (interaction) of these forms of capital plays a crucial role in the way individuals are positioned within the social hierarchy (hiérarchie sociale). Those with high levels of economic and cultural capital are better able to influence social fields (champs sociaux) and dominate others. This interaction ultimately reinforces the reproduction of existing power structures, making it more difficult for individuals from lower social classes to access the same opportunities, regardless of their effort or talent.

Bourdieu’s analysis suggests that capitalism is not only about the accumulation of wealth but also about the maintenance of social distinctions (distinctions sociales), which are sustained by the interplay between economic and cultural capital.

3. Bourdieu’s Critique in The Social Structures of the Economy

In his book, The Social Structures of the Economy (Les structures sociales de l’économie), Bourdieu expands on his critique of economic capitalism by examining how social structures and economic practices are deeply intertwined. He argues that economic systems are not just mechanical entities driven by market forces but are socially constructed (socialement construits) and shaped by culture, power dynamics, and the dispositions of individuals and institutions.

Bourdieu’s key argument in this text is that economic fields (champs économiques) operate in ways that reinforce social hierarchies. While traditional economics tends to focus on the market’s efficiency and the rationality of economic agents, Bourdieu insists that economic action is shaped by habitus and capital, both of which are influenced by the social context. People’s economic choices are not purely rational decisions based on supply and demand but are influenced by social structures, educational background, and symbolic practices.

In this book, Bourdieu also delves into the role of institutions (institutions) in perpetuating economic inequalities. For example, financial institutions, the state, and educational systems play an essential role in shaping the distribution of economic and cultural capital. These institutions, rather than being neutral or objective, are seen as part of the broader structure that reproduces the capitalist system by favoring those with more access to capital and symbolic power.

Bourdieu’s critique in The Social Structures of the Economy focuses on how economic actions and institutions help to preserve the status quo (status quo) by legitimizing social inequalities. These systems are maintained through symbolic violence, which serves to reinforce the idea that social hierarchies are natural and deserved. Thus, Bourdieu does not merely critique economic capitalism in terms of its material effects but in terms of how it shapes perceptions, beliefs, and practices that sustain the broader social order.

XII. The Media and the Reproduction of Cultural Capital

1. The Relationship Between Media and Cultural Capital

Pierre Bourdieu examined the significant role of media (les médias) in the reproduction and distribution of cultural capital (capital culturel). In his analysis, Bourdieu argued that the media functions as a powerful tool in reinforcing social stratifications by distributing cultural capital in a way that favors certain social groups over others.

The media is not merely an outlet for information but a field (champ) of symbolic production where cultural goods, values, and representations are generated, disseminated, and consumed. Media platforms, such as television, newspapers, and later digital platforms, serve as key spaces where cultural distinctions (distinctions culturelles) are established and maintained. By controlling the narratives and the cultural products that are made available, media institutions exercise significant power in shaping how cultural capital is understood and valued by society.

Bourdieu emphasized that the elite groups (groupes dominants) in society, such as those in positions of economic and cultural power, have the means to influence the media landscape. Through their control of media organizations, these elites can define what is considered valuable or prestigious in society. Consequently, cultural capital becomes associated with the tastes, behaviors, and values promoted by the media. For instance, particular forms of art, music, literature, or even fashion become seen as markers of social distinction (distinction sociale) when they are repeatedly endorsed and celebrated in mainstream media.

The media thus helps in reproducing the distribution of cultural capital by selectively promoting and legitimizing certain cultural values, reinforcing existing social hierarchies (hiérarchies sociales), and aligning cultural capital with the tastes and preferences of the dominant classes.

2. The Reproduction of Cultural Values Through the Media

Bourdieu’s theory suggests that the media plays a crucial role in the reproduction of cultural values (reproduction des valeurs culturelles) and societal norms. Media outlets contribute to shaping the public’s perception of what is considered “legitimate” culture, further solidifying the power of the dominant classes (classes dominantes) to define cultural taste and preferences.

According to Bourdieu, media content, including news, entertainment, advertisements, and even social media, serves as a mechanism for the transmission (transmission) of values that align with the interests of powerful social groups. These values are not simply reflected in the content but are actively constructed and communicated through symbolic processes (processus symboliques). For example, the media often presents elite cultural practices as being universal and deserving of admiration, while the cultural practices of marginalized groups may be either ignored or portrayed in a negative light.

The media thus becomes a vehicle (véhicule) through which cultural capital is passed down across generations. By consistently representing certain behaviors, lifestyles, and forms of education as prestigious, media outlets contribute to the reproduction of social inequality (reproduction des inégalités sociales). In this way, media reinforces the dominance (domination) of the upper classes, making it difficult for individuals from lower social classes to access the same cultural capital.

The reproduction of cultural values also works through the portrayal of social norms, such as beauty standards, work ethics, or political ideologies. The media continually presents these norms as “natural” and unquestionable, contributing to the internalization (internalisation) of these ideas by the general public, especially in the lower strata of society.

3. Class and Cultural Distinctions in Media Representations

Bourdieu’s concept of class (classe) and cultural distinctions in media representations is central to understanding how the media perpetuates social divisions. In his analysis, he argued that the media serves as a key institution in the maintenance of symbolic boundaries (frontières symboliques) that separate social classes from one another.

The media represents class distinctions by consistently associating certain cultural forms and practices with specific social groups. For instance, high culture (e.g., classical music, fine art) is frequently portrayed as associated with elite or upper-class (classe supérieure) individuals, while lower-class cultural practices (e.g., popular music, reality TV) are often stigmatized or devalued. Through these representations, the media constructs an image of cultural hierarchy (hiérarchie culturelle) that positions some cultural products as superior to others.

This dynamic reinforces the connection between taste (goût), class (classe), and cultural capital. In Bourdieu’s terms, the media plays a role in legitimizing (légitimer) specific forms of cultural capital that align with the values and tastes of the dominant classes. For example, when certain books, films, or art forms are widely circulated and celebrated by the media, they become elevated as symbols of distinction (symboles de distinction) that signal a person’s social position and education.

Through the continuous reproduction (reproduction) of these cultural distinctions, the media fosters a sense of social belonging and exclusion. Those who consume media content that aligns with the dominant cultural norms are often able to claim higher status in society, while those who engage with alternative cultural forms are marginalized or rendered invisible.

In summary, the media’s role in the reproduction of cultural capital is a central force in maintaining social stratification (stratification sociale). By constantly highlighting certain cultural practices as legitimate while devaluing others, the media acts as a powerful institution that shapes public perception and reinforces the power dynamics between social classes.

XIII. Bourdieu’s Influence on Contemporary Social Theory

1. Bourdieu’s Impact on Contemporary Social Theory

Pierre Bourdieu’s work has had a profound impact (profound impact) on contemporary social theory, influencing a wide range of disciplines, including sociology (sociologie), anthropology (anthropologie), and cultural studies (études culturelles). His theories on cultural capital (capital culturel), habitus (habitus), and symbolic violence (violence symbolique) have become central to understanding how social power is distributed and reproduced across different levels of society.

Bourdieu’s theoretical contributions challenge traditional views of social mobility, power (pouvoir), and inequality (inégalité). His work provides critical insight into how individuals’ social positions (positions sociales) are influenced by capital (capital) and how symbolic forms of domination shape our understanding of social structures. His concept of cultural capital, for example, has allowed scholars to understand how taste, education, and lifestyle choices are not just personal preferences but are deeply embedded in social hierarchies (hiérarchies sociales).

Bourdieu’s theories have been used to explain education systems, cultural production, and the dynamics of power relations (relations de pouvoir) in both Western and non-Western contexts. His critique of economic determinism (critique du déterminisme économique) and his exploration of the symbolic dimensions (dimensions symboliques) of power have made his ideas particularly influential in fields such as social stratification, media studies, and gender studies.

By emphasizing the role of symbolic capital (capital symbolique) in the formation of social identities, Bourdieu’s work has also informed contemporary discussions about identity politics (politique d’identité) and intersectionality (intersectionnalité). The focus on how class (classe), gender, and race intersect and impact social positioning has opened new avenues for understanding complex social phenomena and power dynamics.

2. Modern Applications of Cultural Capital, Habitus, and Symbolic Violence

Bourdieu’s concepts of cultural capital, habitus, and symbolic violence continue to be widely applied and adapted in contemporary research. These concepts have been utilized to analyze a broad range of social practices, from educational systems to media representations and workplace dynamics (dynamiques de travail).

In the field of education, Bourdieu’s theory of social reproduction (reproduction sociale) remains a crucial framework for understanding how schools perpetuate inequalities. His concept of cultural capital explains how students from privileged backgrounds possess advantages in the form of knowledge, taste, and social networks, which give them an edge in academic settings. Researchers have built on Bourdieu’s work to investigate how schools and universities function as sites of cultural reproduction (sites de reproduction culturelle), where students from disadvantaged backgrounds struggle to gain recognition for their own cultural practices.

Bourdieu’s notion of habitus is also applied in contemporary studies to understand how individuals’ personal dispositions and behaviors are shaped by their social context. This concept has been used to explore how cultural practices (pratiques culturelles), including preferences for certain types of music, fashion, or lifestyle choices, reflect an individual’s social position (position sociale) and serve to maintain social boundaries (frontières sociales). Researchers in sociology and cultural studies have examined how habitus influences people’s behavior in various social contexts, from consumer habits (habitudes de consommation) to political preferences.

In addition, Bourdieu’s theory of symbolic violence remains a powerful tool for analyzing how certain cultural practices and social norms (normes sociales) are used to legitimize and maintain power structures. This concept has been particularly useful in gender studies (études de genre) and race studies (études raciales), where scholars have applied it to understand how subtle forms of discrimination and marginalization are embedded in everyday social interactions. Symbolic violence helps to explain how inequalities (inégalités) are perpetuated through culturally ingrained practices that are often taken for granted, such as the representation of women and minorities (représentation des femmes et des minorités) in the media or the unequal distribution of power in workplace settings.

3. The Influence of Bourdieu’s Theories on Sociology and Anthropology

Bourdieu’s influence on sociology (sociologie) and anthropology (anthropologie) has been immense, reshaping the way scholars approach the study of society, culture, and power. His concepts of capital, habitus, and field have become essential tools for understanding how individuals navigate and reproduce their social environments.

In sociology, Bourdieu’s theory of social fields (champs sociaux) has been used to examine various spheres of social life, including education, politics, and the arts. Scholars have adopted Bourdieu’s framework to analyze how power is exercised in different social domains (domaines sociaux), and how individuals and groups compete for resources (ressources) and legitimacy (légitimité). For instance, in the study of politics, Bourdieu’s ideas on social fields have been applied to investigate how political parties and movements operate as fields of power (champs de pouvoir), where different actors fight for influence, often using symbolic capital to gain support and recognition.

In anthropology, Bourdieu’s work has been employed to study the role of culture in shaping human behavior and social organization. Anthropologists have used his concept of habitus to explore how cultural practices are internalized and passed down within communities, shaping individuals’ worldviews and social interactions. This has been particularly useful in studying the ways in which cultural practices are linked to broader social structures (structures sociales) in different societies, whether in terms of kinship, religion, or economic practices.

Bourdieu’s work has also been influential in challenging traditional anthropological notions of cultural relativism (relativisme culturel) by emphasizing the ways in which cultural practices are not simply expressions of group identity but are deeply connected to social power (pouvoir social) and inequality (inégalité). His critiques of the anthropology of culture (anthropologie de la culture) have helped scholars rethink how culture is intertwined with broader structures of domination (structures de domination) and how social hierarchies are reinforced through cultural practices.

In summary, Bourdieu’s work has left a lasting impact on both sociology and anthropology, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding how cultural practices, social power, and inequality are deeply interconnected. His theories continue to be central in contemporary social theory, providing valuable insights into how social structures are reproduced and contested in modern societies.

XIV. Critiques of Bourdieu: Limitations and Controversies

1. Major Critiques of Bourdieu’s Theories

While Pierre Bourdieu’s theories have greatly influenced contemporary social science, they have also faced significant critiques. One of the major criticisms is his concept of determinism (déterminisme), particularly in his analysis of habitus and social reproduction (reproduction sociale). Critics argue that Bourdieu’s theories overemphasize the role of social structures (structures sociales) in shaping individuals, limiting the potential for human agency and the ability for social change. Some scholars claim that his framework tends to portray individuals as mere products of their social environments, thus diminishing their ability to act autonomously (agir de manière autonome).

Another critique revolves around Bourdieu’s notion of cultural capital (capital culturel) and its application to inequality. While it’s argued that this concept has been invaluable in understanding social stratification, some suggest that Bourdieu’s framework doesn’t sufficiently account for individual resistance (résistance individuelle) or alternative forms of capital that may challenge dominant power structures. Critics have pointed out that by focusing heavily on symbolic violence (violence symbolique), Bourdieu sometimes overlooks how individuals and groups engage with or resist cultural norms and hegemonic systems.

Finally, Bourdieu’s theoretical approach (approche théorique) is often seen as overly complex (complexe) and abstract, making it difficult to apply to practical or empirical research. His emphasis on structuralism and symbolic analysis (analyse symbolique) has also led some scholars to argue that his work lacks concrete mechanisms for addressing the real-world consequences (conséquences réelles) of social inequality.

2. Controversies Regarding Structuralist Determinism

Bourdieu’s work has been critiqued for its structuralist determinism (déterminisme structuraliste), which suggests that individuals’ actions and choices are predominantly determined by their social position (position sociale) and the forms of capital (capital) they possess. Critics, particularly from post-structuralist and postmodern perspectives, argue that Bourdieu’s focus on social structures (structures sociales) as determining forces neglects the role of individual agency (agence individuelle). They contend that Bourdieu’s deterministic outlook underestimates the capacity for individuals to exercise choice (exercer des choix) and creativity (créativité) in shaping their lives.

Moreover, Bourdieu’s structuralism has been challenged by those who advocate for more fluid (fluide) or hybrid (hybride) models of social life, where identities (identités) and social positions are constantly changing (en constante évolution). Critics argue that social life cannot always be explained through rigid structural categories and that people may act in ways that do not always reflect their social position or cultural capital.

3. The Limitations of Bourdieu’s Theories and Proposed Solutions

Despite Bourdieu’s groundbreaking contributions, his theories have limitations. One such limitation is that his framework (cadre théorique) does not always provide a clear path for social transformation (transformation sociale). While his analysis of power and social structures highlights how inequalities are perpetuated, Bourdieu does not offer practical solutions for achieving social change (changement social). His work is seen by some as more diagnostic than prescriptive, focused on analyzing the ways in which social order (ordre social) is maintained, rather than how to dismantle it.

Additionally, Bourdieu’s emphasis on symbolic violence (violence symbolique) may obscure the material realities (réalités matérielles) of economic inequality (inégalité économique). Critics argue that Bourdieu’s work may overemphasize the symbolic aspects (aspects symboliques) of power and neglect the importance of economic (économique) and institutional (institutionnel) forces in shaping inequalities. Some scholars propose integrating Bourdieu’s work with more Marxist (marxiste) or class-based (basé sur les classes) analyses to better understand the full range of structural power dynamics (dynamiques de pouvoir structurelles).

Bourdieu’s theories also face criticism for being too Eurocentric (européocentrique). Scholars argue that his focus on Western (occidental) social contexts, particularly his studies in France (France) and Algeria (Algérie), limits the applicability of his concepts to non-Western societies (sociétés non occidentales). Some have called for the development of a globalized (mondialisé) or post-colonial (post-colonial) approach to social theory, one that integrates Bourdieu’s concepts but also accounts for cross-cultural (transculturels) variations in the construction of capital and habitus.

XV. Conclusion: The Lasting Legacy of Pierre Bourdieu’s Theory

1. The Modern Value and Ongoing Impact of Bourdieu’s Theories