1. Introduction: Wittgenstein and the Limits of Language

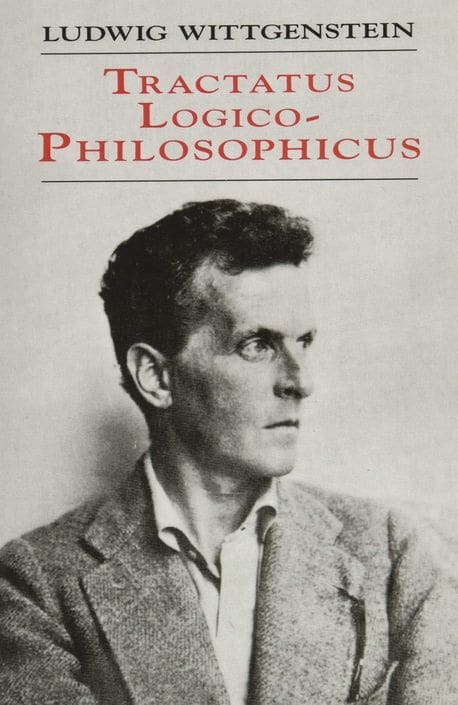

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) stands as one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century. His early masterpiece, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), boldly attempts to chart the limits of linguistic expression and, by extension, the limits of thought and world. In the preface to the Tractatus, Wittgenstein famously declares that “the book will… draw a limit to thinking, or rather – not to thinking, but to the expression of thoughts”. This endeavor led to the Tractatus’ haunting final proposition: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” . In focusing on what cannot be said, Wittgenstein illuminates the unsayable realms that can only be shown or communicated non-verbally. These ideas not only revolutionized analytic philosophy’s approach to language and logic, but also provoked enduring debates about the role of silence, showing, and non-verbal communication in conveying meaning.

1.1 Context and Motivation: Wittgenstein wrote the Tractatus amid the intellectual ferment of early analytic philosophy and the personal crucible of World War I. Philosophers like Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege had made language and logic central to philosophy’s mission, and young Wittgenstein set out to solve philosophical problems by clarifying the logic of language. The Tractatus is the singular book Wittgenstein published in his lifetime, and he initially believed it solved “all the major problems of philosophy” . In doing so, it tackles an age-old question: What are the limits of language? Wittgenstein’s answer would draw a sharp boundary between sense and nonsense, between what can be clearly said in words and what lies beyond the reach of propositional language.

1.2 Focus of the Analysis: This essay undertakes an in-depth analysis of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, with special attention to its exploration of the limitations of linguistic expression and the corollary role of non-verbal “showing”. We will examine Wittgenstein’s philosophical background and influences, dissect the key doctrines of the Tractatus (such as the picture theory of meaning and the sayable/unsayable distinction), and explicate crucial statements like “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world” and “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” The discussion remains neutral and analytical, surveying multiple scholarly interpretations – from the enthusiastic reception by the Vienna Circle to later critiques and Wittgenstein’s own second thoughts in his Philosophical Investigations. Throughout, we will consider how Wittgenstein’s insights shed light on non-verbal forms of communication (gesture, art, silence) as bearers of meaning beyond words.

(Wittgenstein | Language quotes, Bilingual quotes, Learning quotes) An illustration of Wittgenstein’s famous dictum (in French): “The limits of my language are the limits of my universe.” Here, a ladder rises from the fractured globe of the world into a speech bubble, symbolizing the idea that language frames the world we can meaningfully talk about. What lies beyond – the realm of the unspeakable – must be approached by means other than language.

1.3 Outline of this Essay: The analysis is structured into 12 main sections. We begin with Wittgenstein’s biography and intellectual context, highlighting how his life experiences and influences shaped the metaphysical and logical concerns of the Tractatus. We then provide an overview of the Tractatus – its unique structure and its central theses about language picturing reality. Sections are devoted to explaining the picture theory of meaning, the boundaries of language identified in the text (what can be said versus what must be shown), and the profound implications of remaining silent about the unsayable. The latter half of the essay discusses the reception and critiques of the Tractatus, including perspectives from John M. Keynes and the Vienna Circle of logical positivists, as well as Wittgenstein’s own later reconsideration of his early doctrines in the Philosophical Investigations. We further explore how Wittgenstein’s distinction between saying and showing elevates the importance of non-verbal communication – those aspects of meaning conveyed by actions, images, or experiences rather than explicit words. Finally, we consider Wittgenstein’s broader legacy in philosophy and culture, maintaining a balanced view that incorporates multiple scholarly perspectives. By the end, we will see how Wittgenstein, through both his logic and his silences, has challenged us to recognize the limits of language and the significance of what lies beyond.

2. Wittgenstein’s Life and Background

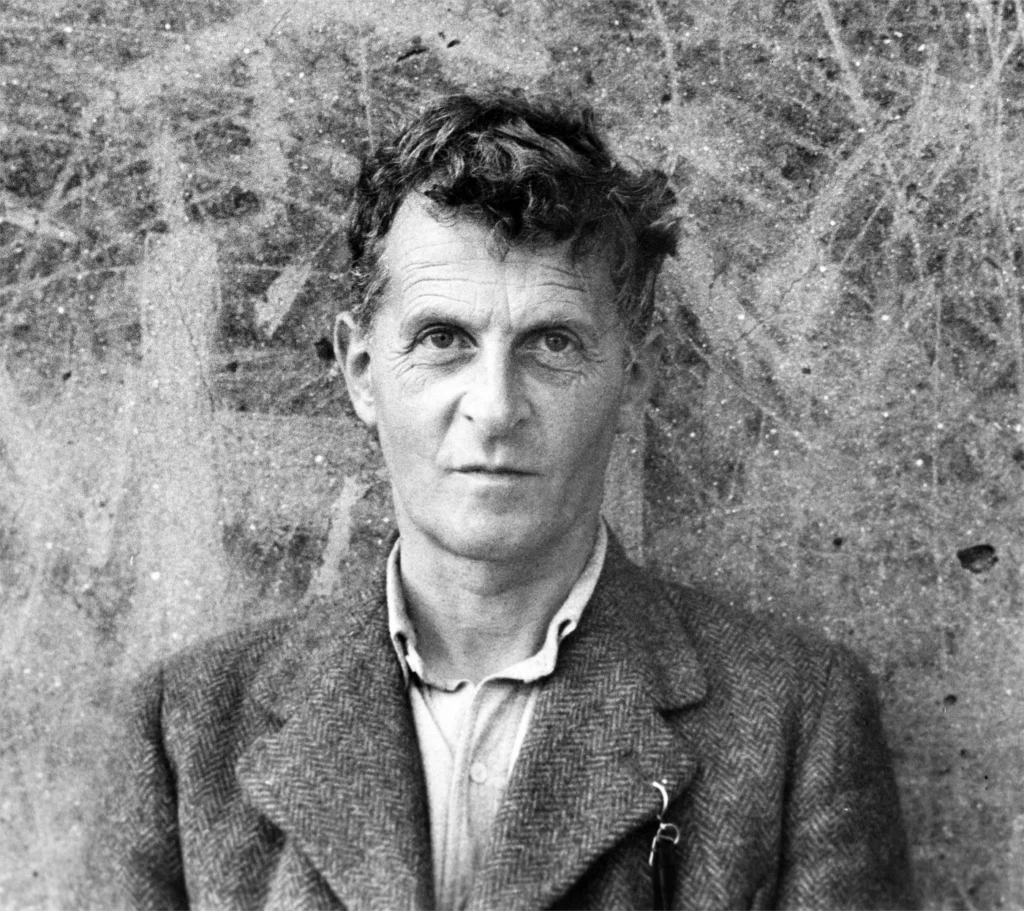

Wittgenstein’s philosophical work cannot be separated from the dramatic contours of his life. Born into a wealthy industrial family in fin de siècle Vienna, Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein was the youngest of eight children (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). His father, Karl Wittgenstein, was a leading steel magnate of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Wittgenstein home was an intellectual and cultural salon frequented by luminaries (the composer Johannes Brahms was a family friend). This rarefied upbringing instilled in young Ludwig both a love of music and a lifelong urge toward “moral and philosophical perfection” (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Yet darker currents ran through the family: three of his older brothers died by suicide, a tragic fact that weighed on Wittgenstein’s psyche and sense of ethics . Profoundly self-critical and ascetic by temperament, Wittgenstein developed an almost religious dedication to honesty and clarity in thought – traits that would later characterize his philosophical work.

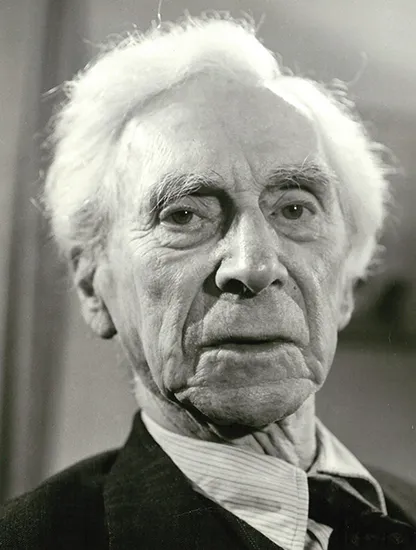

2.1 From Engineering to Philosophy: In 1908, Wittgenstein left Vienna to study mechanical engineering in Berlin, and then in 1908–1911 he conducted research on aeronautics in England ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). It was the foundations of mathematics that truly captivated him, however, leading him to the door of logician Gottlob Frege in 1911. Frege’s advice to Wittgenstein was pivotal: he urged the young engineer to go to Cambridge and study with Bertrand Russell, then the world’s leading philosopher of logic ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). Wittgenstein arrived at Cambridge University in 1911 and made an immediate impression. Russell at first found him “obstinate and perverse” but “not stupid,” and within months decided “I shall certainly encourage him. Perhaps he will do great things…I feel he will solve the problems I am too old to solve.” ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ) ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). Indeed, Russell’s prophetic instinct was correct – Wittgenstein would soon tackle the very problems of logic and language that preoccupied the Cambridge philosophers.

2.2 Cambridge and Influences: At Cambridge, Wittgenstein engaged in intense conversations with Russell and GE Moore, and even John M. Keynes (better known as an economist) moved in the same circles ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). Wittgenstein was a strange, magnetic figure – a passionate, solitary soul who would retreat for months to rural Norway to think in isolation . By 1913, having distilled from Russell all he could, Wittgenstein left Cambridge. He inherited a large fortune upon his father’s death and, in a characteristic act of renunciation, gave it all away to his siblings and others (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). When World War I erupted in 1914, Wittgenstein volunteered for the Austro-Hungarian Army as a foot-soldier on the Russian front . Remarkably, he carried philosophy with him into the trenches – along with Leo Tolstoy’s Gospel in Brief (a devotional book he read obsessively) – and kept notebooks of thoughts that would seed his first major work (Wittgenstein | Mists on the Rivers–). He displayed conspicuous bravery in battle, earning several medals , but also underwent existential crises. The war’s horrors and Tolstoy’s Christian teachings deepened Wittgenstein’s concern with ethics, death, and the mystical, which later found expression in the enigmatic final sections of the Tractatus.

2.3 Writing the Tractatus in War: In 1918, as the war neared its end, Lieutenant Wittgenstein was captured and held as a prisoner of war in Italy ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). During these final war years, he completed the manuscript of the Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung, later published in English as Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. The Tractatus is a terse, cryptic work composed of numbered propositions – a format reflecting the precise, crystalline structure Wittgenstein saw in logic and reality. Cambridge colleagues worked to get it published: Bertrand Russell wrote a laudatory introduction, though Wittgenstein himself was dissatisfied with Russell’s interpretation. When the book finally appeared in 1922, it immediately struck many as a work of genius. In Wittgenstein’s home city of Vienna, members of the nascent Vienna Circle of logical positivists hailed the Tractatus as an anti-metaphysical manifesto. In Cambridge, John Maynard Keynes announced Wittgenstein’s return from war with an almost messianic excitement: “Well, God has arrived. I met him on the 5:15 train,” Keynes wrote to his wife in January 1929 (‘One of the Great Intellects of His Time’ | Ray Monk | The New York Review of Books), signaling the awe Wittgenstein inspired in his contemporaries.

2.4 Retreat from Academia: Ironically, by the time others began grappling with the Tractatus, Wittgenstein himself believed he had “finally solved” the essential problems of philosophy. In 1919, he resigned any further academic work and trained as a village schoolteacher in rural Austria. For several years he lived an austere life, teaching elementary schoolchildren and reportedly imposing strict discipline (his intensity did not entirely suit the classroom). He also applied his technical skills to design a modernist house in Vienna for his sister Gretl – a project he completed with fanatical attention to architectural detail (down to crafting doorknobs). These odd interludes reflected Wittgenstein’s attempt to find ethical meaning beyond theoretical work. Yet by the late 1920s, doubts crept in about whether the Tractatus had truly settled everything. In 1929 Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge, now in his late 30s, somewhat chastened and ready to re-enter philosophical debate.

He famously told Russell and Moore (who examined him for a PhD by treating the Tractatus as his thesis) that they could never really understand his work – but nonetheless, he was awarded the doctorate. Keynes’s facetious greeting of Wittgenstein as “God” underscored the reverence he commanded, but Wittgenstein was about to embark on a thorough re-examination of his own earlier ideas.

2.5 Later Years and Philosophical Revisions: Wittgenstein remained at Cambridge as a fellow and eventually a professor (succeeding Moore in 1939). Throughout the 1930s and 40s, he labored on new philosophical investigations that would only be published posthumously. He lived modestly, even working during World War II as a hospital orderly in London and a lab assistant in Newcastle.

In these decades, Wittgenstein gradually broke with the approach of the Tractatus, developing a “later philosophy” centered on ordinary language, meaning-as-use, and philosophical “therapy” for conceptual confusions. By 1949 he had drafted the manuscript of Philosophical Investigations, his second great work .

Wittgenstein died of cancer in 1951, leaving instructions to publish the Investigations, which appeared in 1953. His life had come full circle: from the youthful certainties of the Tractatus, through a period of silence and practical life, to a mature re-engagement with philosophy’s puzzles. As he lay dying, Wittgenstein’s last words were poignantly simple: “Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life”.

This austere genius, who renounced wealth and comfort in pursuit of truth, had indeed lived on his own terms. His biography – “an obsession with moral perfection” and a commitment to live out his philosophy (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) – illuminates the fervor behind his philosophical contributions. With this context in mind, we can now turn to the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus itself, the product of Wittgenstein’s early brilliance and the crucible of war.

3. Philosophical Influences and Metaphysical Outlook

Wittgenstein’s early philosophy as embodied in the Tractatus was shaped by a unique confluence of influences: the logical rigor of Frege and Russell, the metaphysical and ethical yearnings of Schopenhauer and Tolstoy, and his own quest for absolute clarity. Understanding these influences helps in grasping the Tractatus’ take on metaphysics – a view that is at once austere (in dismissing traditional metaphysical claims as nonsense) and mystical (in acknowledging that some truths lie beyond language).

3.1 The Logical Builders – Frege and Russell: From Gottlob Frege, Wittgenstein inherited a reverence for logic and an appreciation of precise semantic distinctions. Frege’s work taught him that language could be analyzed with mathematical rigor, distinguishing sense from reference and identifying the formal “logic” lurking in ordinary propositions. Bertrand Russell, Wittgenstein’s direct mentor, provided both inspiration and a foil. Russell’s own program, known as logical atomism, sought to reduce complex propositions into simpler “atomic” facts and logical relations – an approach that strongly influenced the structure of the Tractatus. Indeed, many of the Tractatus’ key ideas can be seen as developments of Russell’s theories, such as the idea that the world consists of facts that language mirrors. However, Wittgenstein quickly surpassed his teacher in boldness. Russell later noted that Wittgenstein “had a spirit of passionate rigor, by contrast with which my own seemed sloppy”, and that Wittgenstein “was perhaps the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived” (as recounted in Ray Monk’s biography) ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). Under Russell’s wing, Wittgenstein absorbed a commitment to logic and science – a conviction that philosophical problems required analysis of language and logical form. This influence is evident in the Tractatus’ core premise that “philosophical problems arise from misunderstandings of the logic of language”. Wittgenstein took the “logical turn” farther than anyone: he set out to delineate, once and for all, the formal limits of language, thought, and reality.

3.2 The Metaphysicians – Schopenhauer and Mysticism: Alongside analytic rigor, Wittgenstein carried a metaphysical sensibility inherited from philosophers like Arthur Schopenhauer. As a teenager, Wittgenstein read Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation, which left a deep imprint. Schopenhauer’s opening line – “The world is my idea (representation)” – finds an echo in Tractatus proposition 5.6: “The world is my world”. In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein engages with solipsism, the view that only one’s own self and experiences are certain. He makes the cryptic remark that “what the solipsist means is quite correct, only it cannot be said, but it shows itself” (Wittgenstein & Mysticism: Grasping What Cannot Be Said).

This paradoxical endorsement of solipsism’s truth alongside its unsayability is very much in the spirit of Schopenhauer (who regarded the world as a projection of the self) and even of Kant’s unknowable “thing-in-itself.” Moreover, Schopenhauer had emphasized the transcendental nature of ethics and aesthetics – themes Wittgenstein would adopt. Wittgenstein’s upbringing and wartime experiences also infused him with a quasi-religious drive to find meaning beyond the factual world. He was intensely interested in religion (though not orthodox), and believed, as he later said, that “every problem [could be] seen from a religious point of view” .

During World War I, Wittgenstein found comfort in Tolstoy’s commentary on the Gospels, which reinforced his sense that the ultimate values (ethical, spiritual) are not captured by scientific or everyday language. Thus, even as the Tractatus puts severe limits on what can be meaningfully said, it nods to what lies beyond those limits – the unsayable realm of value, which Wittgenstein calls the mystical.

3.3 Logical Atomism and the World as Facts: One of the Tractatus’ basic metaphysical tenets is that the world is not a collection of things, but a collection of facts. This idea was drawn from Russell’s logical atomism and possibly from the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Boltzmann’s scientific philosophy, but Wittgenstein gives it crisp expression in the opening of the Tractatus: “1. The world is all that is the case. 1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things.” (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). By “fact” (Tatsache in German), Wittgenstein means an existing state of affairs – a specific arrangement of objects. The Tractatus posits that reality has atomistic structure: there are simple objects (never fully described in the book, but conceived as the logical atoms of the world) that combine into states of affairs; these states of affairs, in turn, make up the totality of what is the case (the world). Wittgenstein’s metaphysics here is both reductive (all complex phenomena reduce to combinations of simples) and formalist (what matters is the form of combination). He does not allow any talk of supernatural entities, abstract universals, or metaphysical essences – such talk, for him, lacks sense. Yet, unlike a crude materialist, Wittgenstein does not say reality is just physical objects; rather, it’s the facts (the true propositions) that “constitute” the world. This nuanced view was his way of reconciling metaphysics with the new logic: whatever can be said about the world must ultimately refer to facts composed of simple elements, mirrored by the structure of language. If one tries to say more – e.g. to ask “What is the nature of the world as a whole?” or “Are there values beyond facts?” – one crosses the boundary of sense. Thus, in the Tractatus, metaphysics as a discipline is largely dismissed. Any statement purporting to describe “the essence of the world” or the existence of God or the meaning of life is literally nonsensical according to Wittgenstein’s criteria (since it cannot be built out of simple, empirically meaningful propositions).

In Wittgenstein’s austere metaphysical outlook, everything that can be thought at all can be thought clearly – and everything that can be expressed can be expressed clearly (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library). What cannot meet this clarity test falls outside the domain of meaningful language.

3.4 Anti-Metaphysics and the Transcendental: It might seem that Wittgenstein is a strict positivist who simply banishes all traditional metaphysics. It is true that the Tractatus strongly influenced the logical positivists, who read it as affirming that propositions of metaphysics (and even of ethics and theology) are literal nonsense, useful only to be “passed over in silence.” Wittgenstein indeed says in 4.003 of the Tractatus that most propositions of philosophers – about “the Good,” “the Beautiful,” etc. – are nonsensical, arising from a misuse of language.

“The mystical” (das Mystische), he writes, “is not how the world is, but that it is”, implying that wonder at existence cannot be put into words within the world. However, unlike some positivists, Wittgenstein did not mock or trivialize the unsayable – instead, he considered it of profound importance. He famously told his friend Ludwig von Ficker that the real point of the Tractatus was an ethical one .

In a letter, he explained that the book’s value lies in what it does not say: it demonstrates the limits of language, thereby illuminating (albeit indirectly) the domain of ethics, aesthetics, and the meaning of life, which are beyond those limits. In other words, Wittgenstein’s metaphysical stance is that the deepest things (value, God, the meaning of the world) are transcendental: they exist (or are felt), but cannot be stated as facts. He writes, for example, “It is clear that ethics cannot be expressed. Ethics is transcendental. (Ethics and aesthetics are one and the same.)” (TLP 6.421, not in the main text we cite, but often quoted). Thus, while the Tractatus draws the boundary of language tightly around factual discourse, it leaves a silence filled with significance. This dual attitude – ruthless dismissal of metaphysical propositions as Unsinn (nonsense), coupled with reverence for what is unsayable – is a hallmark of Wittgenstein’s early philosophy. It reflects the intersection of his analytic training and his moral-spiritual sensibility. As one commentator put it, Wittgenstein’s work holds that “anything normative, supernatural or (one might say) metaphysical must, it therefore seems, be nonsense” according to his theory of meaning, yet the Tractatus itself acknowledges that those very “nonsense” things (like ethics, the metaphysical subject, etc.) are shown rather than said. We will explore this paradox of saying vs. showing in detail later.

3.5 Conception of Philosophy – A New Method: Another important aspect of Wittgenstein’s contribution is his conception of what philosophy should do. Influenced by both Russell’s analytic methods and by his own conviction that philosophy had to purify thought, Wittgenstein saw philosophy not as a doctrine but as an activity. In the Tractatus, he asserts that philosophy is not natural science and must stand apart from factual discourse. Its task is critical: “to show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle,” as he later phrased it ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ).

In the early period, this meant using logical analysis to reveal how language functions, thereby dissolving the classic puzzles of philosophy. The Tractatus itself, he says, is like a set of steps: “My propositions serve as elucidations… anyone who understands me eventually recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has climbed through them – on them – beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.)” (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia) (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia). This striking metaphor of Wittgenstein’s ladder encapsulates his philosophical approach: he gives the reader a structured way to think through philosophical problems, but insists that in the end these propositions are not orthodox “truths” but tools to be discarded once the insight is gained. The real goal is a kind of enlightenment – seeing the world aright by recognizing what can and cannot be said. In summary, Wittgenstein’s early philosophical worldview is one of extreme clarity and humility. All legitimate knowledge, he holds, can be expressed in clear propositions (ultimately those of natural science and logic) (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library). Beyond that lies a realm that, though inexpressible, is not irrelevant – it is, in fact, where questions of value, meaning, and consciousness reside. This tension between logical positivism and mysticism in Wittgenstein’s influences sets the stage for the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, to whose content we now turn.

4. Overview of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Structure and Key Theses

The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is a compact but extraordinarily ambitious work. In a mere 75 pages of numbered aphorisms, Wittgenstein attempts nothing less than a final solution to philosophy’s riddles. The book’s structure is itself noteworthy: it consists of seven main propositions, numbered 1 to 7, with decimal-numbered sub-propositions elaborating each point in a hierarchical outline. For example, proposition 1 is “The world is all that is the case.” Its immediate comment is 1.1 “The world is the totality of facts, not of things,” and further elaboration continues as 1.11, 1.12, etc., until proposition 2. Then proposition 2, 3, and so on, each with their chain of sub-points, lead systematically to the final standalone proposition 7. This logical outline format mirrors the book’s content: Wittgenstein is displaying in the very form of his writing the layered, logical architecture of reality and language. It’s a work that progresses from ontology (the nature of the world) through the nature of representation and logic, finally to ethics and the limits of language.

4.1 A Ladder of Propositions – Structural Overview: The seven primary propositions of the Tractatus serve as milestones of Wittgenstein’s argument. They can be summarized as follows:

- 1: The world is everything that is the case.

- 2: What is the case (a fact) is the existence of states of affairs.

- 3: A logical picture of facts is a thought.

- 4: A thought expressed in language is a proposition with sense.

- 5: Propositions are truth-functions of (elementary) propositions (logical composition).

- 6: The general form of a truth-function is described (and this yields the general form of a proposition). This leads to the boundaries of language and logic.

- 7: Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

This skeletal outline is fleshed out by the sub-propositions. The Tractatus reads almost like a series of cryptic mathematical theorems about reality and language. It was written in an oracular style partly because Wittgenstein believed “whatever can be said at all can be said clearly” and thus he strove to eliminate any excess verbiage (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library). The result is dense and often perplexing. (Not for nothing did Wittgenstein concede in the preface that the book might only be understood by someone who had already had similar thoughts (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library).) Yet, a coherent vision emerges: Wittgenstein believes he has identified the logical essence of language, thought, and world, and by doing so, has shown what can be meaningfully said and what cannot.

4.2 Proposition 1 – The World and Facts: The Tractatus opens with the stark pronouncement: “1. The world is all that is the case.” Everything that exists or occurs is encapsulated in “the case” – a phrase meaning a fact or state of affairs. Proposition 1.1 immediately clarifies: “The world is the totality of facts, not of things.”

This is a rejection of any metaphysics that treats objects or substances as the fundamental reality. Instead, facts (something is the case) are fundamental. For example, “the cat is on the mat” is a fact (if true), involving objects “cat” and “mat” in a certain relation “on.” The objects (cat, mat) by themselves are not the world; the fact that one is on the other is the world’s substance. Thus, the Tractatus posits a world of facts which can be pictured and expressed by propositions. This view underpins Wittgenstein’s approach: by focusing on facts, he aligns ontology with language, since language too is fact-stating (when meaningful). Every fact can be mirrored by a proposition that is either true or false depending on whether that fact is the case. Consequently, the structure of reality (facts composed of objects) will be mirrored by the structure of language (propositions composed of names). This sets the stage for the picture theory to come.

4.3 Propositions 2 and 3 – States of Affairs and Representation: Propositions 2 and 3 delve deeper into what facts are and how thoughts represent them. A state of affairs (Sachverhalt) is a combination of simple objects (2.01), and it is the existence or non-existence of state of affairs that constitute facts (2.06–2.08). For example, objects A and B can either stand in relation R (forming the state of affairs “A R B”) or not – if they do, that is a fact; if they don’t, the negation of that state of affairs is a fact. Wittgenstein assumes there is a fixed inventory of objects and possible configurations, giving the world a kind of logical space of possibilities (2.011–2.014). Human thought enters in proposition 3: “In a proposition a thought finds an expression that can be perceived by the senses.” (3.1) (Lecture Supplement on Wittgenste). A thought is essentially a picture of a possible state of affairs (3.5). Here Wittgenstein introduces his seminal Picture Theory: “The propositional sign, applied and thought out, is a picture of reality” (3.0 was an earlier version of this idea). According to 3.2, a proposition is composed of names that correspond to objects, arranged in a structure that mirrors the arrangement of objects in the state of affairs if it is true (Lecture Supplement on Wittgenste) (Lecture Supplement on Wittgenste). Thus, proposition 3.21 says the configuration of simple signs (names) in the proposition “corresponds” to the configuration of objects in reality (Lecture Supplement on Wittgenste) (Lecture Supplement on Wittgenste). This is the heart of Wittgenstein’s representational metaphysics: language works by picturing facts. A thought (a proposition in the mind) has sense because it depicts a possible situation. If the world matches that depiction, the proposition is true; if not, it is false (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now). Crucially, a proposition must share a form with the fact it represents – Wittgenstein calls this logical form. But logical form itself is not explicitly stated: it is shown by the proposition. (We will return to this in the say/show distinction.)

4.4 Proposition 4 – The Picture Theory of Language: Proposition 4 is a central pivot of the Tractatus. It asserts: “A proposition is a picture of reality. (A proposition is a model of reality as we imagine it.)” (TLP 4.01) (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). This is the explicit statement of the Picture Theory of meaning. All meaningful propositions “picture” states of affairs or facts (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). How do words function as pictures? Wittgenstein invites us to consider simple pictorial examples: a geometric diagram, a map, or even a toy model. Imagine I draw a map for a friend to my house, marking turns and landmarks (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now) (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now).

The drawing’s lines and shapes stand for roads and buildings; the spatial relations among the lines (the map’s form) correspond to the spatial relations of the actual streets. The map can be true or false – it might mislead if I drew it wrong – but it represents a possible configuration of the world (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now) (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now). Similarly, a proposition like “A is to the left of B” uses the relationship between the names “A” and “B” and the relational phrase “…is to the left of…” to picture a possible spatial fact between the corresponding objects. Wittgenstein even references a court case where a miniature model was used to reconstruct a car accident: the model with toy cars and dolls literally pictured the various possible arrangements to determine which one corresponds to the actual crash (picture theory — Insights and Updates — The Literacy Bug) (picture theory — Insights and Updates — The Literacy Bug). For Wittgenstein, language does this in abstract: the proposition, through syntax (word order, logical structure), creates a model of reality. The elements of the proposition (words) are like elements of a picture; their arrangement encodes a state of affairs. This is why Wittgenstein says the proposition has sense (Sinn) insofar as it presents a situation in logical space (Wittgenstein & Mysticism: Grasping What Cannot Be Said) (Wittgenstein & Mysticism: Grasping What Cannot Be Said). Truth and falsity then depend on comparison with reality: “A picture agrees with reality or not; it is correct or incorrect, true or false” (TLP 2.21–2.223).

Importantly, Wittgenstein emphasizes that a picture must have something in common with what it depicts – namely, logical form. “What any picture must have in common with reality, in order to be able to represent it correctly or incorrectly, is logical form,” he writes (TLP 2.18). This shared form is what enables the picture (or proposition) to stand in for the fact. However, logical form itself cannot be a thing we name; it is an implicit feature. “The pictorial relationship consists of the correlations of the picture’s elements with things,” says TLP 2.13. But “the picture cannot place itself outside its representational form” (TLP 2.174). In short, language can depict any reality that shares its form, but language cannot say what that form is – it can only show it by the structure of meaningful propositions. (This foreshadows the unsayable nature of logical form in proposition 4.12 and 4.1212, where Wittgenstein notes “propositions show the logical form of reality” and “What can be shown, cannot be said.” We’ll unpack this later.)

4.5 Propositions 5 and 6 – Logic and the Limits of Language: Having set up the idea that atomic propositions picture atomic facts, Wittgenstein moves to how complex propositions are built and how logic operates. Proposition 5 introduces truth-functions: “A proposition is a truth-function of elementary propositions” (5. and 5.3). Essentially, all of ordinary language’s statements can be reduced to truth-functional combinations (using operators like “and”, “or”, “not”, etc.) of elementary propositions that directly picture atomic facts. This was Wittgenstein’s solution to deal with complexity: at bottom, there is a set of indivisible propositions (each asserting an atomic fact). All other propositions are just truth-functional compounds of these. Logic, then, does not add content; it links propositions in valid ways. For example, “It is raining and it is cold” is a truth-function of two simpler propositions “It is raining” and “It is cold.” In Wittgenstein’s view, logic is tautological – it doesn’t concern contingent facts but rather the scaffolding of language. Proposition 6 states the general form of all propositions and by extension the form of all logical expressions. One of the most important sub-points is 6.1: “The propositions of logic are tautologies.” That is, pure logical propositions (like “Either it is raining or it is not raining”) do not say anything about the world; they are necessarily true given the structure of language, and thus they show the structure of language rather than state facts. This is pivotal: it means logical truths lie at the boundary of language – they are sensical in a way (since they are part of the calculus of language), but they don’t convey information about reality. They are empty of content, yet illuminate form. From here, Wittgenstein draws his stunning conclusions about the limits of language: if we try to say anything that is not an empirical proposition or a logical tautology, we end up with nonsense. Ethics, metaphysics, even the very statements of the Tractatus itself, do not fit the form “p is the case” or a truth-functional combination thereof – so by his own criterion, these sentences are pseudo-propositions. By proposition 6.5 and 6.54, Wittgenstein prepares the reader: his entire treatise is a kind of ladder to be thrown away. Proposition 7 then arrives: a single, austere line – “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”.

In summary, the Tractatus argues that meaningful language comprises pictures of facts, combined by logical operations. We can meaningfully talk only about the facts of the world and the logical relations between propositions. Anything else – aesthetics, ethics, the meaning of life, the metaphysical essence of the world, even the logical form itself – cannot be put into meaningful propositions. The book itself, through its structured propositions, attempts to guide the reader to see this insight. Wittgenstein’s structural approach was so unique that Russell noted “certainly it deserves… to be considered an important event in the philosophical world”. By the end of the Tractatus, Wittgenstein believes he has drawn the limits of language precisely, showing that beyond those limits lies only silence. To fully grasp these claims, we now examine two of the most important aspects of the Tractatus: the Picture Theory of meaning in detail, and the distinction between what can be said and what can only be shown.

5. Language as Picture: The Picture Theory of Meaning

At the heart of the Tractatus is Wittgenstein’s picture theory of language, a bold explanation of how words bear meaning. The theory holds that a meaningful proposition is a picture (Bild) of a possible state of affairs in reality. In Wittgenstein’s own words: “The proposition constructs a world with the help of a logical scaffold, and therefore one can see from the proposition alone whether it is true or not, if it is true” (TLP 4.02). In this section, we unpack the picture theory and illustrate its implications with examples. By doing so, we also lay groundwork for understanding why some aspects of reality – like logical form or ethics – cannot be captured by such pictures.

5.1 Propositions as Pictures of States of Affairs: We’ve seen Wittgenstein’s claim that “a proposition is a picture of reality” (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). But what exactly does it mean for a sentence to be a “picture”? We normally think of pictures as visual images or drawings. Wittgenstein uses “picture” in a more abstract sense: any structured representation that corresponds point-for-point to the structure of something it represents. For a simple illustration, consider a geometric diagram. If I draw three points connected by lines to form a triangle, that drawing is a picture of a possible arrangement of three actual objects related in a triangular way. Or consider a musical score: the written notes stand in spatial relations on the stave that correspond to temporal and tonal relations in the music. The score is a picture (in a rule-governed way) of the music’s structure. Similarly, Wittgenstein asserts that a sentence in language is a picture of a situation. The elements of the sentence (words) correspond to objects, and the syntax (how the words are arranged) corresponds to how those objects are related in the situation (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now) (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now). The picture theory thus sees language as isomorphic to reality: there is a one-to-one matchup between the parts of a proposition and the parts of the possible fact it depicts.

5.2 An Everyday Example – The Map and the Territory: To make this concrete, Wittgenstein (and interpreters) often use analogies like maps or diagrams. Suppose I sketch a simple map: a line for a road, with a cross at one point to represent a church and a small square to represent a shop. This map can be true or false of the actual village. If the church is actually north of the shop but my map shows it south, then the map is an incorrect (false) picture of the village. But even a false map represents something – it depicts a possible configuration (just not the actual one). Wittgenstein’s point is that meaning is tied to this representational capacity: the map has meaning (it’s not just random ink) because we interpret its elements as standing for real things in a certain arrangement. In the same way, a sentence like “The church is south of the shop” has meaning because we understand “the church” to refer to an object (the church), “the shop” to another object, and “…is south of…” to denote a spatial relation. The sentence thus projects a certain arrangement (church south-of shop). If that arrangement obtains in reality, the sentence is true; if not, it’s false (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now) (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now). Either way, the sentence makes sense because it pictures that arrangement. Notice that truth-value (true or false) is separate from sense (having meaning). As Wittgenstein insists, “a picture [or proposition] represents something that could be the case whether or not it actually is the case” (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now) (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now). A false statement is a picture of a state of affairs that does not exist, but it is still a valid picture (just as a painting of a fictional scene still has meaning). This criterion was central to Wittgenstein’s thought: to be meaningful, a proposition must rule in and rule out certain possibilities – it must have a determinate truth-condition. “What a picture represents is its sense,” he would say, and “the agreement or disagreement of the picture with reality constitutes its truth or falsity” (TLP 2.221, 2.222).

5.3 Elements of the Picture – Names and Objects: In the Tractatus’ framework, the basic components of a proposition are names. A name (Name) denotes an object (an irreducible element of reality). For Wittgenstein, a simple proposition (an elementary proposition) is one that consists of names arranged in a relation, corresponding directly to a state of affairs (a combination of objects). For example, an imagined elementary proposition might be something like “A stands in relation R to B” – here “A” and “B” are names of objects, and “R” signifies a relation. The proposition as a whole is an elementary picture: [A –R– B]. If the objects referred to as A and B do stand in relation R, the proposition is true. If they do not, it’s false. Wittgenstein posits that all complex propositions ultimately break down into these atomic ones. In this way, the ultimate building blocks of meaning are names and the logical form that connects them. An important aspect of the picture theory is that names themselves have no meaning in isolation – their meaning is the object they stand for, but one can’t even say which object without a propositional context. The Tractatus emphasizes that only a proposition has sense (3.3); a name by itself designates an object but doesn’t say anything. This is analogous to how on a map, a single symbol like a dot has meaning only when one knows what it’s supposed to represent (e.g. a dot could represent a city or a campsite depending on the map’s conventions). And a single dot alone doesn’t convey a proposition – one needs at least two and some spatial relation to picture something like “City A is west of City B.” Thus, meaning arises from structure.

Wittgenstein encapsulates this idea with the notion of logical form shared between language and reality. He writes: “In order for a picture to represent a certain fact, it must have something in common with that fact. In the picture and the fact, this common element is the form of representation.” (TLP 2.16–2.17). In practice, when you understand a sentence, you grasp its form: you know how the parts hang together and thereby what situation it purports to depict. For Wittgenstein, logical syntax (the rules of putting words together) guarantees that a well-formed sentence maps onto a possible configuration of things. If you violate syntax, you get nonsense – akin to a scribble that doesn’t correspond to any coherent scenario. This is why Wittgenstein demanded a perspicuous notation for logic; he even presents truth-tables and logical notation in the Tractatus as showing the structure of logical propositions (4.31–4.Truth tables are themselves diagrams that show how the truth of a complex proposition depends on its atomic parts ([PDF] The Place of Saying and Showing In Wittgenstein’s Tractatus and …). In a sense, a truth-table is a picture of a proposition’s logic – another instance of his picture concept, but applied to logical form.

5.4 Independence of Truth from Representation: One key feature of pictures is that they can be misleading or false while still being meaningful. Wittgenstein underscores that “a picture is linked with reality; it reaches up to it,” but it is not reality itself (TLP 2.1511). We are not constrained by actuality when forming pictures (Pictures and Nonsense | Issue 58 | Philosophy Now). Just as an artist can paint a unicorn though none exists, language can describe scenarios that do not obtain. This independence is crucial because it explains how we can speak hypothetically, talk about fiction, or simply make false statements, yet still use meaningful language. Wittgenstein writes: “It is essential to a proposition that it can communicate a possible situation without stating whether it actually exists” (paraphrasing TLP 4.024). The meaning is the possible situation; the question of truth is separate. This decoupling shows the power and limitation of language: language can depict any logically possible configuration of objects, but it cannot guarantee that configuration is real. This also hints at something profound: language and thought’s limits are the limits of possibility. If something is literally inconceivable (doesn’t even form a coherent picture), we cannot speak of it meaningfully. Wittgenstein famously states “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world” (TLP 5.6) – suggesting that what you cannot even formulate in language, you cannot properly think or “have” in your world (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). This doesn’t mean reality is created by language, but that our cognitive access to reality is bounded by the structures our language can represent. This tenet will become important when we consider the ineffable: if ethical values or metaphysical truths do not correspond to any arrangement of objects (any state of affairs), then by the picture theory they cannot be represented in language at all – they are outside the world of language, in a sense.

5.5 Strengths and Limits of the Picture Theory: The picture theory was revolutionary in how it tied meaning to a verifiable condition – a precursor to the positivists’ verification principle that a sentence’s meaning is its method of verification (Wittgenstein,Tolstoy and the Folly of Logical Positivism | Issue 103 | Philosophy Now) (Wittgenstein,Tolstoy and the Folly of Logical Positivism | Issue 103 | Philosophy Now). It elegantly explained why nonsense arises when we string words without structural correspondence to a possible situation. However, it also has limits. For one, it applies most straightforwardly to factual, descriptive language – statements of “this is how things are.” It struggles with other uses of language (questions, commands, poetry, etc.), though Wittgenstein largely sets those aside in the Tractatus. Moreover, the picture theory implies a sort of minimal empiricism: as one commentator notes, “According to this theory propositions are meaningful insofar as they picture states of affairs or matters of empirical fact. Anything normative, supernatural or metaphysical must, it seems, be nonsense.” (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). This leads to a self-referential problem: Does the picture theory itself make sense as a proposition? The Tractatus talks about objects, facts, logical form – but according to its own strictures, sentences like “There are objects” or “Names refer to simple objects” do not directly picture a state of affairs (they attempt to say something about the form of all states of affairs). By Wittgenstein’s standard, such philosophical statements are nonsensical. Indeed, he acknowledges this tension: “My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognizes them as nonsensical” (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). The picture theory itself is part of the ladder that must be tossed after climbing. So while the picture theory clarifies what ordinary meaningful statements are, it undercuts itself if taken as a literal doctrine. Wittgenstein was aware of this and built the Tractatus to self-destruct gracefully, leaving behind only the insight it conveyed.

In spite of its paradoxes, the picture theory captures something powerful about communication: much of language’s success lies in showing us a possible world so that we can check it against the actual world. When I say “There is a red apple on the table,” I invite you to imagine that scene and then look to confirm if reality matches. If you see no apple, you understand the proposition (its picture) enough to declare it false. The mechanism by which language hooks onto the world is, for Wittgenstein, the shared logical form between proposition and fact. This notion leads directly to the next major theme: the distinction between what language can explicitly say and what must instead be shown or indicated without saying. After all, as we’ve hinted, logical form itself – the very glue of the picture – is something that cannot be straightforwardly stated within the system. It is shown by the structure of meaningful propositions. We now turn to this crucial “say/show” distinction, which ties into Wittgenstein’s broader point about the limits of language.

6. The Limits of Language: What Can Be Said and What Must Be Shown

One of the most important – and subtle – contributions of the Tractatus is the distinction between saying and showing. Wittgenstein argues that there are things which cannot be put into words, but which nevertheless manifest themselves (or “show themselves”) in language or experience ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ) ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). This distinction is intimately connected to the limits of language: it delineates the boundary between propositions with sense (which say something about the world) and the unsayable aspects of reality (which can only show themselves). Understanding this concept is key to grasping why Wittgenstein ends the Tractatus in silence and why he believed certain realms (ethics, aesthetics, metaphysics, even logic itself) lie beyond the reach of literal language.

6.1 Drawing the Boundary of the Sayable: In Wittgenstein’s view, language properly used can only say factual things – it can state that such-and-such is the case. For instance, all of science, all daily observations, any claim about what exists or what happens, falls into this category of what can be said. These are the propositions of natural science, which Wittgenstein considered the legitimate output of language (TLP 6.53). By contrast, if one tries to use language to talk about the form of language, the essence of the world, the meaning of life, God, the Good, etc., one ends up producing pseudo-propositions. They may look like meaningful statements, but according to Wittgenstein, they do not picture a concrete state of affairs and thus have no genuine sense (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). As he succinctly puts it in the Tractatus: “What can be said at all can be said clearly; and whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library). The first clause underscores that language is suited for clear factual description; the second clause tells us to abstain from attempting to speak about what lies outside that domain.

But Wittgenstein does not imply that the unspeakable is irrelevant or non-existent – only that it cannot be captured by words. Instead, some things are shown. For example, take logical form. We encountered that the logical form (the structural relationship between language and world) is something we cannot state in a proposition. One cannot say “The structure of this sentence is such-and-such” in the same sentence to fully describe its own structure – any attempt leads to an infinite regress or incoherence. Instead, the structure is exhibited by the sentence itself. It is shown by a well-formed proposition which, by being well-formed, demonstrates it has a certain logical form (even though the proposition doesn’t say “I have logical form X”). In TLP 4.121, Wittgenstein writes: “Propositions show the logical form of reality. They display it.” (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). And in 4.022: “Language disguises thought; so much so, that from the external form of the clothes one cannot infer the form of the thought beneath, because the external form of the clothes is not designed to reveal the form of the body, but for entirely different purposes.” (In other words, the grammar of language doesn’t explicitly tell you its logical form; you have to discern it.) This leads to the famous line 4.1212: “What can be shown, cannot be said.” (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

6.2 The Realm of the Unsayable: What are the kinds of things that Wittgenstein consigns to the category of “can only be shown”? We’ve mentioned logical form (the form of representation) as one. Another is the existence of objects or the general structure of the world. For example, I can say “This object is red” (a particular factual statement), but I cannot meaningfully say “There are objects” in the abstract or “Object A has objecthood.” The latter attempts to step outside particular facts and talk about the universe of discourse as a whole. According to Wittgenstein, a statement like “There are objects” doesn’t picture a state of affairs – it tries to talk about the very precondition of talking about anything. Thus it’s nonsensical in his strict sense (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). However, does that mean it isn’t true in some sense? Wittgenstein would say it’s not false; it’s just a misuse of language. The reality that “there are objects” is shown by the meaningfulness of names in propositions. Each time we successfully use a name to refer to something, we show that the ontology of objects is in place. But we do not say it.

Most notably, ethics, aesthetics, and the meaning of life fall in the unsayable realm. Wittgenstein was deeply concerned with these, yet he asserts in TLP 6.421: “Ethics and aesthetics are one.” They are transcendental, and “[Ethical propositions] cannot be expressed.” He famously wrote (in an often-cited letter) that if someone tried to write a book on ethics as a series of propositions, “this book would, with an explosion, destroy all the other books in the world.” The point being: genuine ethical value is not something that can be stated as an empirical proposition. For instance, you cannot say “Murder is wrong” in the same factual manner as saying “The sky is blue.” Ethical statements don’t picture states of affairs – they purport to express absolute values. In the Tractatus framework, that makes them literally nonsensical. But, and this is crucial, Wittgenstein did not dismiss ethics as worthless. Instead, he held that ethics “is transcendental” (TLP 6.421). In a sense, ethics shows itself in how we live, in our attitudes, in the aspects of the world we choose to pay attention to. Similarly, the mystical (das Mystische) refers to those features of reality that aren’t facts in the world but the sheer existence of the world, or what lies beyond its edges. “There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical.” (TLP 6.522) ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ) ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). This powerful statement (which Wittgenstein placed just before the final proposition) encapsulates his view: the existence of the world, the felt quality of life, the sense that something is meaningful – none of these are propositions we can utter, but they are manifest in our experience of the world. The meaning of life, if there is one, would thus show itself in how one lives or sees the world, not in something one can say.

6.3 What “Showing” Means: To clarify, when Wittgenstein says something is “shown,” he does not mean it is shown in the sense of giving empirical evidence. It’s more akin to implicit in something. For example, the rules of grammar are shown by how we speak correctly, though we may not be able to explicitly state all those rules. In a broader sense, phenomena of consciousness – say, the feeling of a melody or the aspect one perceives in art – might be said to show something (an emotional truth, a perspective) that no verbal description fully captures. Wittgenstein had a strong interest in the inexpressible aspects of music and art. He once remarked, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” but he was an avid listener of music and reader of poetry, indicating he believed silence (or art) could communicate what words cannot. The Tractatus itself is constructed to lead the reader to an insight which is not explicitly stated by any proposition in the book – the insight, arguably, that the quest to “say the unsayable” is a confusion, and that one must let certain things be. In that sense, the Tractatus attempts to show the reader the limits of language by exemplifying them. It performs its philosophy rather than just stating it.

Another example often given is solipsism (the idea that only I exist). In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein does a remarkable maneuver: he argues that if one properly understands the language, solipsism reduces to mere realism. He says: “The world of the happy man is a different one from that of the unhappy man” (TLP 6.43) implying perspective matters, but then notes “What the solipsist means is quite correct, only it cannot be said, but it shows itself.” (Wittgenstein & Mysticism: Grasping What Cannot Be Said). The truth the solipsist intuits – that I experience the world from a unique first-person perspective – cannot be put into a factual statement like “Only I exist,” which is nonsense. However, it shows itself because the concept of “world” in the end is for me the world I experience. In other words, the limits of language (and thought) are also the limits of my world (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy), and this is “my” world inasmuch as I am the one thinking. But I cannot say that in a meaningful way that excludes others’ existence. Wittgenstein thus respects the subjective viewpoint but also indicates it’s not a matter for propositional language.

6.4 Consequences for Philosophical Problems: The saying/showing distinction leads to a deflationary view of many classic philosophical debates. For instance, consider the attempt to define the meaning of life or to prove the existence of God in propositions. Wittgenstein would say these attempts will always either result in nonsense or triviality. If someone describes God in terms of worldly facts, they degrade the concept to a thing within the world (which theists themselves would say God is not). If they try to speak of God as beyond the world, then by Tractatus standards they are talking nonsense (since beyond the world lies only what shows itself, not what can be said). Thus, one must be silent, meaning one must not attempt to build a metaphysical theory in language. However, one might show reverence or live religiously – those are non-verbal modes of dealing with the unsayable. (Indeed, Wittgenstein had a lifelong fascination with religion and often spoke of approaching problems “from a religious point of view,” though he did not endorse any church – he likely saw religious forms of life as ways of showing a stance toward the mystical). In philosophy, this approach implies that many traditional questions are actually misposed. Wittgenstein claims that “most of the propositions and questions of philosophers arise from our failure to understand the logic of our language” (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). By clarifying what language can do, he believed, these pseudo-questions would vanish. For example, asking “What is the meaning of the world?” is, in his framework, a nonsensical question – the world is everything that is the case, it has no further “meaning” describable within it. The meaning or value lies outside it (if anywhere), which we cannot speak of. So the proper philosophical attitude is to recognize such questions as unanswerable by propositions and thus avoid them. In Wittgenstein’s metaphor, philosophy’s task is to show the fly out of the fly-bottle – to free us from the linguistic traps where we buzz around in confusion ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ).

6.5 “Nonsense” with a Purpose: A critical nuance is that Wittgenstein distinguishes between different kinds of nonsense. There is ordinary gibberish which is just a mistake, and then there is illuminating nonsense – the kind of carefully crafted nonsense that the Tractatus itself comprises (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). He saw his own propositions as nonsensical in the strict sense (because they talk about the logical form, ethics, etc.), but hoped that by reading them, one could see something true. In this sense, the Tractatus uses language to point beyond language. It’s almost a Zen-like paradox: using words to induce an understanding that words can’t express. As one scholar noted, “the Tractatus pulls the rug out from under its own feet” (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy), and Wittgenstein intended that. Those final propositions (6.54 and 7) enact the dismissal of the ladder of propositions (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia) (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia). The reader, having climbed with Wittgenstein through these statements, ideally reaches a vantage point where they can let go of the statements themselves and just see the world rightly – with the distinction between what can be said and what must remain unsaid.

To conclude this section, Wittgenstein’s stance in the Tractatus is that language has sharp limits: it can depict concrete facts clearly and logically, but it cannot speak about its own structure or the higher matters of value and meaning. Those higher things “make themselves manifest” in other ways ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). This insight leads directly to the last proposition, often taken as the motto of the Tractatus:

“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library)

In the next section, we will focus on interpreting that famous injunction and how it was received. It is a statement that has resonated far beyond technical philosophy, encapsulating a kind of philosophical humility. We will also see how Wittgenstein’s later work in Philosophical Investigations moves away from the rigid say/show framework of the Tractatus, yet still grapples with the interplay between language and the unspoken.

7. “Whereof One Cannot Speak…”: Interpreting the Tractarian Silence

Proposition 7 of the Tractatus – “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library) – is at once the book’s most quoted line and its most enigmatic. This single sentence stands alone as the final pronouncement of Wittgenstein’s early philosophy. In this section, we examine what this famous dictum means in context, how it encapsulates the Tractatus’ stance on the unsayable, and how it has been interpreted (and sometimes misinterpreted) by philosophers. We will also explore Wittgenstein’s metaphor of throwing away the ladder, which directly precedes proposition 7, indicating that the entire Tractatus has a self-consuming nature. Finally, we consider the neutrality and rigor with which Wittgenstein approaches this ultimate limit – the silence that lies beyond language.

7.1 The Final Proposition in Context: By the time the reader reaches proposition 7, Wittgenstein has established that any attempt to talk about the limits of language or the meaning beyond facts will result in nonsense. The only sensible course is to remain silent on those topics. Proposition 7 thus appears as the logical terminus of the book’s journey: having delineated what can be said (facts of the world, propositions of science, logical relations), Wittgenstein simply instructs us to abstain from saying anything else. In the preface, he already foreshadowed this attitude: “The book’s whole meaning could be summed up somewhat as follows: What can be said at all can be said clearly; and whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library). Notably, he placed this motto (including the clause about speaking clearly) right at the start as a clue to his readers. Thus, proposition 7 is not a throwaway line – it is the crystallization of Wittgenstein’s therapeutic goal: to show the reader which questions are meaningless so that one will stop asking them.

To “must be silent” doesn’t necessarily mean one should never think about ineffable things – rather, it means one should not attempt to encapsulate them in propositions as if they were ordinary facts. It urges a kind of intellectual discipline: a recognition of the boundary where language fails. Some have read this as a stern, almost positivist command to dismiss anything outside scientific discourse. Indeed, the logical positivists of the Vienna Circle took “must be silent” to endorse their view that statements of metaphysics, religion, etc., are not just wrong but cognitively meaningless. They thus eagerly dropped all talk of the “mystical” and focused only on empirical verification (Wittgenstein,Tolstoy and the Folly of Logical Positivism | Issue 103 | Philosophy Now) (Wittgenstein,Tolstoy and the Folly of Logical Positivism | Issue 103 | Philosophy Now). However, Wittgenstein’s own intent seems more nuanced. His silence is not a scornful elimination, but a respectful quietude regarding things words cannot capture. Right before proposition 7, at 6.522, he acknowledges the mystical — “indeed, there are things that cannot be put into words” ( Ludwig Wittgenstein (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) ). So the mandate for silence is not to say “there is nothing beyond language,” but to say “if there is something beyond, we cannot speak of it.”

7.2 The Ladder Metaphor – Throwing Away the Propositions: One of the most illuminating passages of the Tractatus comes just before the final silence, in proposition 6.54. Wittgenstein writes: “My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has used them – as steps – to climb beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.)” (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia) (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia). And then: “He must overcome these propositions, then he sees the world rightly.” (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia) (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia). This remarkable passage reveals Wittgenstein’s self-awareness of the paradoxical nature of his own text. The Tractatus is the ladder – a series of propositions that themselves attempt to say things that, by the book’s end, are classified as unsayable. Why write them then? The idea is that the reader needs to be brought to an understanding of the limits of language from the inside, as it were. By going through the motions of philosophy (speaking about logic, world, self, etc.), Wittgenstein leads the reader to a point where they realize these motions were in a sense illusory. Once that realization dawns, the propositions have done their work and can be discarded. All that remains is wordless understanding: “seeing the world rightly.” (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia).

This metaphor of the ladder emphasizes an experiential component to Wittgenstein’s philosophy. It’s not enough to just be told “you can’t talk about X”; one has to struggle through it and then feel the correctness of remaining silent. Wittgenstein believed that once you reach that vantage point, your perspective on what is important in life and philosophy changes fundamentally (you “see the world rightly”). Some commentators (like Cora Diamond and James Conant in the so-called “resolute” reading of the Tractatus) take this very seriously and argue that Wittgenstein meant for us to throw away every proposition of the book, i.e., not to treat even the picture theory or any earlier thesis as a leftover theory. In this view, the Tractatus leaves no positive doctrine – only an activity of clarification that ultimately negates itself (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Other commentators (the more “traditional” reading) think Wittgenstein did leave something like the picture theory or the idea of ineffable truths intact. But either way, all agree the ladder passage indicates that Wittgenstein saw his own words as a kind of device, not final dogmas.

7.3 Meaning of “Must Be Silent”: The phrase “must be silent” (in German “schweigen”) can be read both as a logical necessity and as a normative injunction. Logically, if something is literally unspeakable (because it doesn’t meet the conditions of sense), then silence is the only option. Normatively, Wittgenstein is advising philosophers to stop trying to do the impossible. This has often been related to an ethical stance for doing philosophy: one should practice intellectual humility. Instead of endlessly speculating in obscure metaphysical language, Wittgenstein’s approach says: clarify what you can; for the rest, appreciate its ineffability. Some have connected this with a kind of Zen or apophatic tradition (negative theology): the idea that ultimate truths (like God in negative theology, or ultimate reality in Buddhism) can only be approached by saying what they are not, and finally by silence. Wittgenstein’s own outlook had some quasi-spiritual undertones. He closes the preface by saying he thinks he has “finally solved” the philosophical problems “to show how little is achieved when these problems are solved” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library) (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library). In other words, even solving all logical problems leaves the real questions of life untouched – and those are precisely the ones that must be shown or met with silence. This lends Whereof one cannot speak… a somewhat poignant resonance: it’s not the triumphant dismissal that some logical positivists imagined, but perhaps a bittersweet acknowledgment that what truly matters (ethics, value, the mystical) lies beyond our theorizing.

7.4 Reception and Misunderstandings: The slogan “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent” took on a life of its own in 20th-century thought. It’s often quoted in discussions of language’s limits. The Vienna Circle loved the first part (the elimination of the unsayable) but tended to ignore Wittgenstein’s reverence for what is beyond. They famously equated “meaningful” with “scientifically verifiable” and consigned everything else to the silent scrap heap, perhaps not appreciating that Wittgenstein himself did not think nonsense = garbage in all cases, but sometimes meaningful-in-a-different-way (i.e., showing). Keynes, in introducing Wittgenstein’s return, quipped on the silence by calling him “God” who had come to lay down limits (‘One of the Great Intellects of His Time’ | Ray Monk | The New York Review of Books). Others in Wittgenstein’s circle, like G.E. Moore, struggled with the idea that the Tractatus’ statements are nonsense. Moore famously asked Wittgenstein to clarify: are you saying these Tractatus propositions are plainly nonsense or just that “in an important sense” they are nonsense? Wittgenstein responded: “I mean nonsense.**” He was adamant – no metaphysical truth sneaked in through the backdoor. This stark position baffled many early readers. Some thought maybe Wittgenstein wanted to convey ineffable truths through the Tractatus (a “ladder” to see God, perhaps). Others, especially later interpreters, emphasized that Wittgenstein’s goal was mainly to cure us of philosophical confusion (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

One fruitful way to see proposition 7 is as a therapy for the reader: by the time you accept it, you’ve let go of the pseudo-questions. The proof of success is that you no longer have the urge to speak of what cannot be spoken. In practical terms, it means that as a philosopher you redirect your energy: instead of constructing grand metaphysical theories, you might focus on analyzing language, or simply acknowledge the wonder of life without trying to pin it down verbally.

7.5 Seeing the World Aright: Wittgenstein’s claim that after throwing away the ladder “he will see the world aright” (Wittgenstein’s ladder – Wikipedia) suggests a kind of enlightenment – perhaps recognizing that the world is just the totality of facts (not a metaphysical structure with hidden meanings), and that one’s task is to accept it. This aligns with what he notes earlier as the “accept and endure” attitude (Cora Diamond’s term) (Wittgenstein, Ludwig | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy): if the essence of the world is simply “This is how things are,” then the proper response is not theoretical, but practical – acceptance. Indeed, Wittgenstein ends one of his few remarks on ethics in the Tractatus with: “The solution of the problem of life is seen in the disappearance of the problem” (TLP 6.521). This cryptic line echoes proposition 7: when you truly understand, the question dissolves, and you are left with silence (but also peace). We might say Wittgenstein’s Tractatus enacts a philosophical quietism: not in the sense of never asking questions, but of knowing when to stop and be quiet. It is the ultimate expression of intellectual integrity for him: if you cannot speak (clearly) about it, don’t speak at all.

In summary, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent” is both a logical maxim and an ethical posture in Wittgenstein’s philosophy (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus/Preface – Wikisource, the free online library). It marks the end point of the Tractatus’ argument that language has limits, and it invites the philosopher (and the reader) to abide by those limits. Far from being a negation of meaning in life, it’s intended to clear the ground so that what is truly meaningful might be appreciated without distortion. The next part of our discussion will examine how Wittgenstein’s ideas, as radical as they were, prompted reactions and critiques – for instance, by Keynes and the Vienna Circle as mentioned, and how Wittgenstein himself re-evaluated some of these positions in his later work Philosophical Investigations.

8. Non-Verbal Communication and the Transcendence of Language

Up to now, our analysis of the Tractatus has emphasized a stark division: language deals with facts, and non-verbal “showing” accounts for what language cannot say. In this section, we delve into the role of non-verbal communication as implied by Wittgenstein’s philosophy and as understood in broader terms. While Wittgenstein himself, in the Tractatus, doesn’t speak of “communication” in the ordinary sense (his focus is on representation and logic), his distinction between saying and showing suggests that many aspects of human understanding occur beyond spoken or written words. We will discuss how gestures, images, art, and other non-linguistic forms can convey meaning, and we will connect this to Wittgenstein’s later thoughts in the Philosophical Investigations on how context and practice (often non-verbal) give language its life. In doing so, we see a more complete picture of human language: not just a formal system of propositions, but one part of a richer tapestry of communication that includes the unspoken.

8.1 The Scope of Non-Verbal Communication: Non-verbal communication encompasses a wide array of human expressive activity: facial expressions, eye contact, gestures, body language, tone of voice, silence, art, music, ritual, and so on. These are carriers of meaning that do not fit neatly into propositional language. Modern communication studies estimate that a significant portion of information in face-to-face interaction is conveyed non-verbally – for example, tone and body language can drastically change the meaning of the same sentence (sincere vs. sarcastic, etc.). Wittgenstein’s Tractatus itself would consider those aspects as part of the “phenomena” of the world that can’t be fully captured by literal description. For instance, the tone in which something is said shows the speaker’s attitude, which might not be explicit in the words. A simple “oh, great” can be genuine or sarcastic, and one only knows from the non-verbal cues. In this sense, what is shown often complements what is said, even in everyday communication.

Even more, there are messages we convey entirely without words. A shrug of the shoulders can mean “I don’t know or I don’t care.” A glance can signal agreement or warning. These are part of the “language” of human interaction, albeit not language in the strict linguistic sense. Wittgenstein’s early work doesn’t analyze these, but his later work does observe such things. In Philosophical Investigations, he notes “Suppose someone is groaning with pain; we ask ‘Why are you groaning?’ – ‘Because I’m in pain.’” The groan shows pain directly; the verbal report is almost secondary. Indeed, Wittgenstein challenges the idea of a private language by pointing out that pain behavior (like groaning) is how we learn words like “pain” – essentially, we interpret the non-verbal cues. So non-verbal expressions are integral to how language gains meaning: they tie words to reality via shared human reactions (this is part of Wittgenstein’s later argument that meaning is rooted in “forms of life”).

8.2 Showing in Art and Action: Wittgenstein’s category of “what can only be shown” invites us to consider how art, music, and actions convey what discursive language cannot. Take music: Wittgenstein (who was a skilled amateur musician) once remarked that you could not replace a piece of music with a verbal description of it – music expresses something in its own medium. A melody can show joy, melancholy, tension, resolution, in a way no statement can. Similarly, a painting might communicate an atmosphere or insight without any words. For example, Edvard Munch’s The Scream shows anguish graphically; one doesn’t need a caption. These forms of communication resonate with Wittgenstein’s notion of the mystical: art often aims to show aspects of human experience (emotions, the sublime, the tragic) that lie beyond straightforward language.