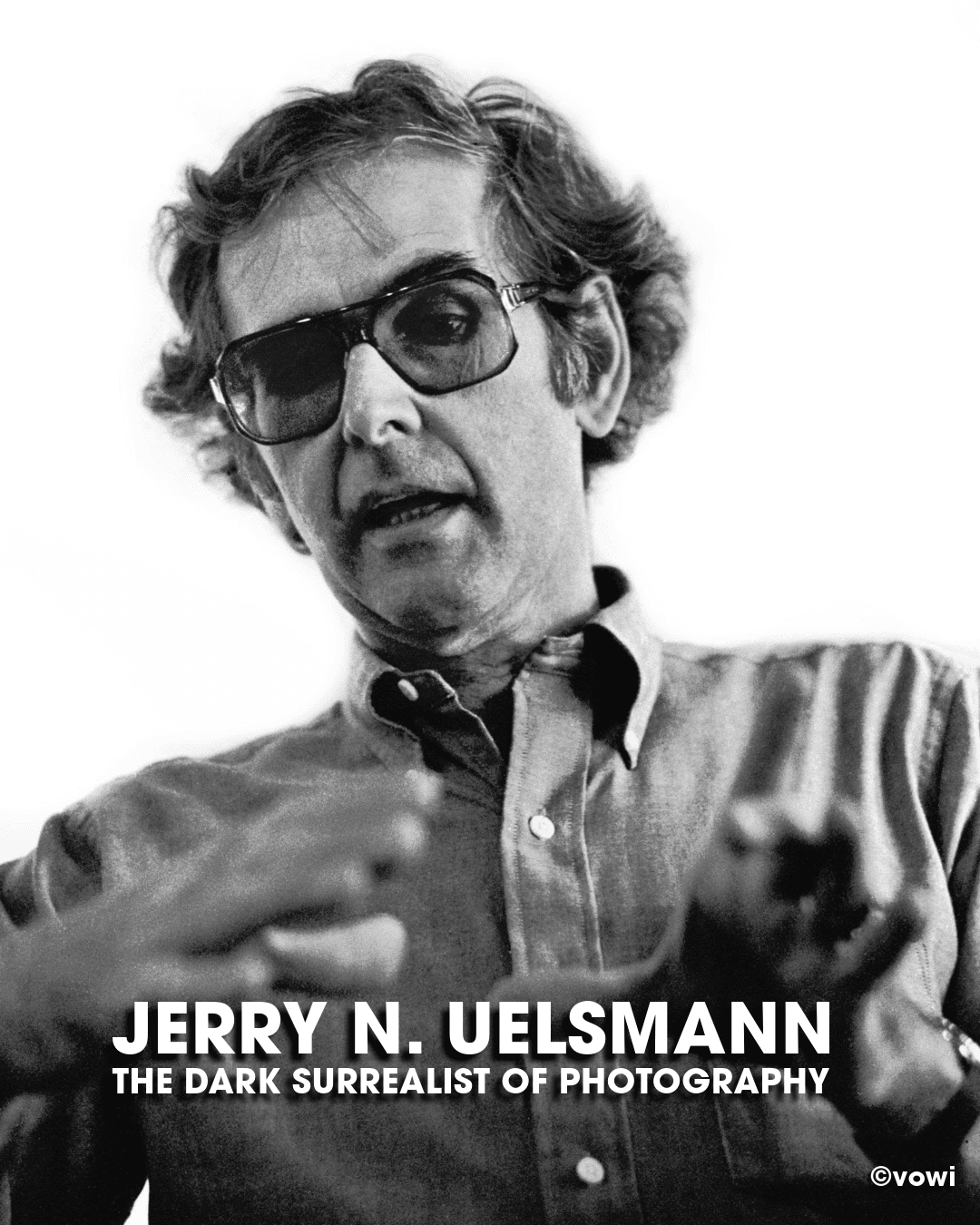

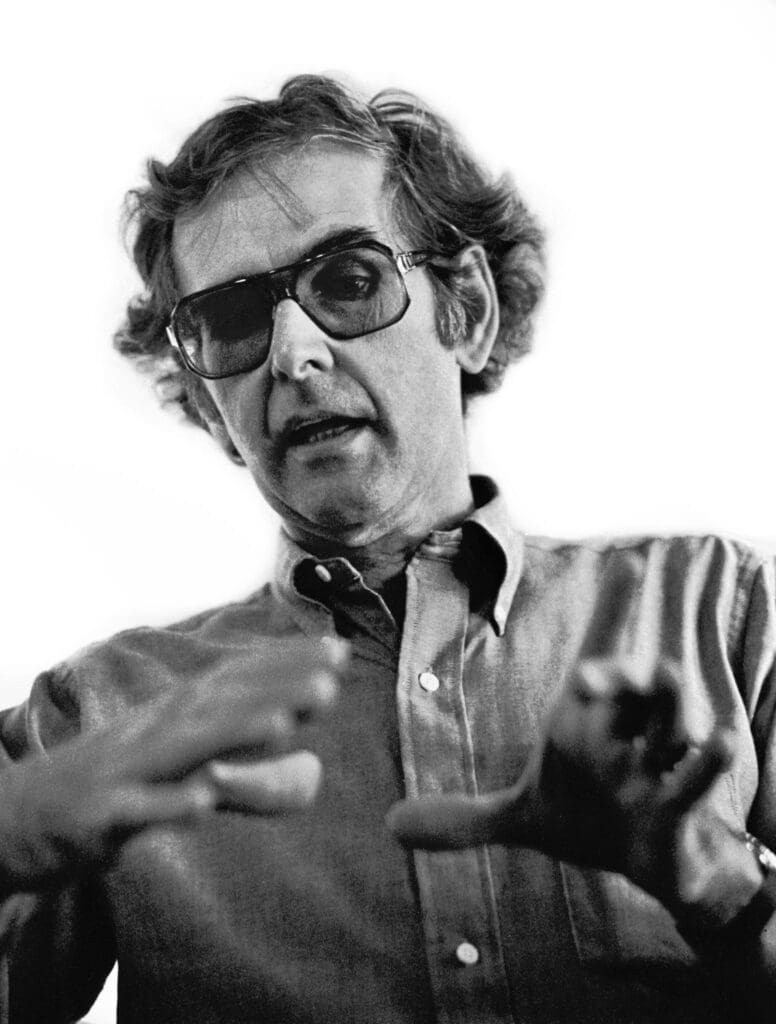

Jerry N. Uelsmann (1934–2022) was an American photographer who revolutionized the art of photography in the 1960s by creating surreal, dreamlike photomontages entirely in the traditional darkroom

Decades before digital editing tools existed, Uelsmann blended multiple negatives to conjure hallucinatory scenes that have “more in common with Salvador Dalí and René Magritte than Ansel Adams”

His flawlessly crafted black-and-white images defied the era’s prevailing “straight photography,” presenting instead mysterious visual narratives rich with symbolic and psychological meaning

Celebrated as a “darkroom alchemist” for his mastery of analog techniques

Uelsmann opened new frontiers for photography as a medium of imaginative expression and influenced generations of artists who followed

The sections below explore his life and influences, the characteristics of his work, his innovative working methods, his artistic philosophy, and the impact he had on other artists.

Life and Early Influences

Jerry Norman Uelsmann was born in Detroit, Michigan, on June 11, 1934. He was the second son of a grocery store owner and discovered photography as a serious interest during his teenage years

While still in high school, Uelsmann worked part-time as an assistant to a wedding photographer, gaining practical experience with cameras and darkroom basics

In 1953, he enrolled at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) with the initial intent of becoming a portrait photographer

However, the creative environment at RIT dramatically expanded his vision of what photography could be. He studied under renowned figures like Minor White and Beaumont Newhall, and alongside talented peers (including future notable photographers such as Bruce Davidson and Pete Turner) he “embraced the broader potential of the medium as a means of creative self-expression”

Minor White, in particular, imparted a critical lesson: the camera could do more than document reality – “it did have the potential of transcending the initial subject matter,” as Uelsmann recalled

This idea that a photograph could reveal something deeper than the surface would profoundly influence Uelsmann’s artistic direction.

After receiving his B.F.A. from RIT in 1957, Uelsmann pursued graduate studies at Indiana University. There he earned his M.S. and M.F.A. by 1960, studying under photography educator Henry Holmes Smith, who further shaped Uelsmann’s approach to photography as a creative and experimental art form

Smith encouraged open-ended experimentation and was known for challenging his students. In one class discussion, Uelsmann boldly critiqued a composite image by artist Arthur Segal, saying “I can do it better,” which only strengthened his resolve to push the limits of technique

At Indiana, Uelsmann also took numerous art history courses that exposed him to the work of Surrealist artists like Magritte, Max Ernst, and photographer Man Ray – influences he found “immediate and enduring”

Immersion in Surrealism’s fantastical imagery and the idea of an “inner-directed” art (art driven by personal vision rather than external reality) resonated with Uelsmann

These early influences – from visionary mentors to surreal and symbolic art – set the stage for Uelsmann’s own imaginative photographic style.

In 1960, upon completing his MFA, Uelsmann began a long teaching career at the University of Florida in Gainesville

Joining the faculty as an assistant professor of art, he helped found the Society for Photographic Education in 1962 and soon gained attention for his unorthodox image-making

The early 1960s photographic establishment was still dominated by a purist philosophy (exemplified by the likes of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston) that valued sharp, unmanipulated images of the natural world

Uelsmann, in contrast, was part of a new wave of young photographers who challenged these orthodoxies. He later noted that he, Duane Michals, and Robert Heinecken were at “the forefront of photographers who challenged the accepted aesthetics back in the ’60s and ’70s and created a new paradigm of what photography could be”

Uelsmann’s own paradigm-breaking work — assembling multiple negatives into seamless new images — would soon catapult him to international fame. By 1967, he had his first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, making him one of the first photographers of his generation to be so honored

That same year he received a Guggenheim Fellowship to support his “experiments in multiple printing techniques in photography”

Uelsmann’s early life journey from a curious Detroit teenager to a trailblazing art photographer was defined by absorbing diverse influences and a willingness to defy conventions.

Photographic Characteristics

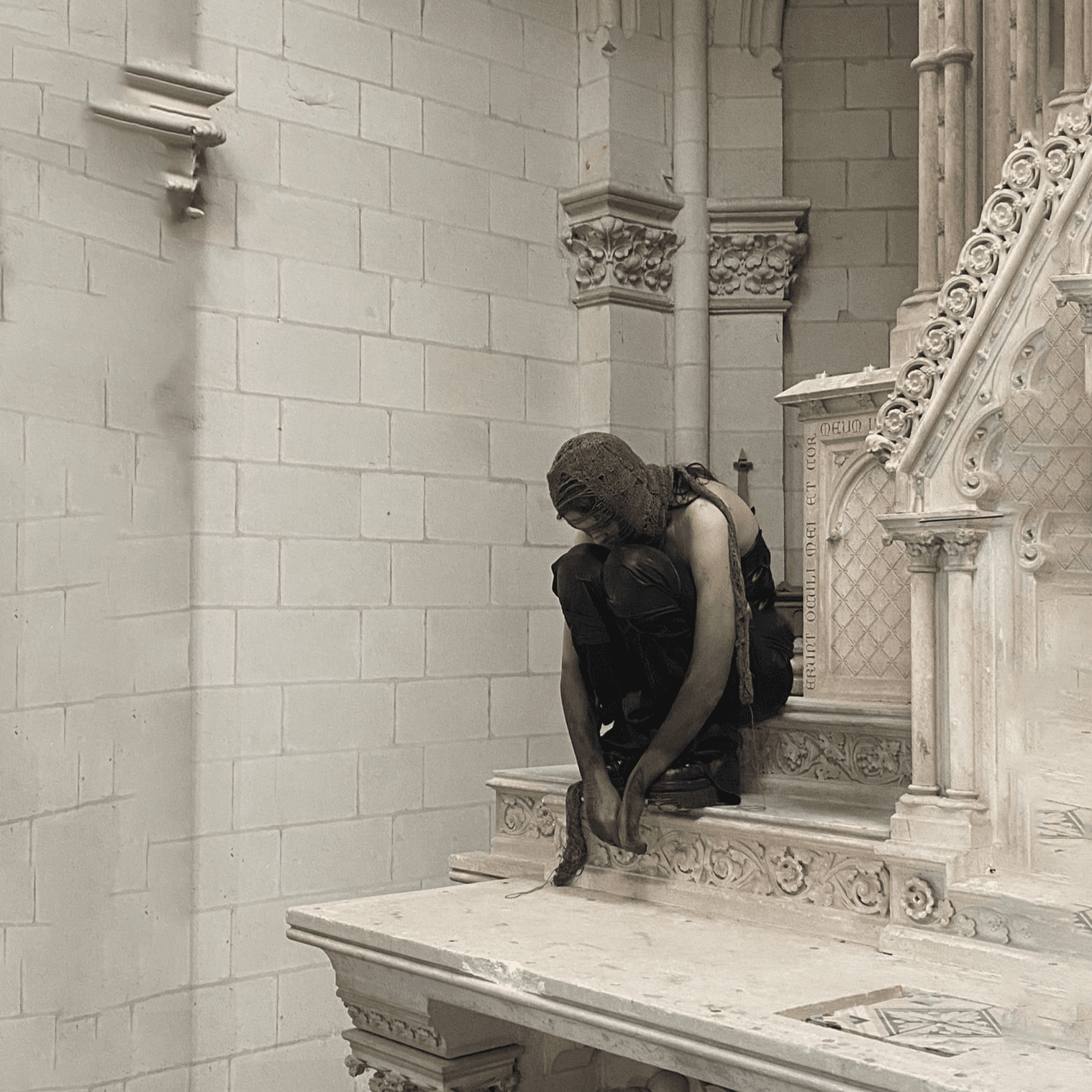

Uelsmann’s photographs are immediately recognizable for their surreal, dreamlike quality and meticulous craftsmanship. Working exclusively in black and white, he created composite images that seamlessly merged disparate elements – human figures, animals, landscapes, clouds, architecture – into otherworldly scenes. The resulting pictures often have a haunting or mysterious mood, earning Uelsmann a reputation as a kind of dark surrealist whose work is as eerie as it is beautiful. Curators have described his 1960s photomontages as “unsettling alternatives” to the era’s straight photography, depicting “hallucinatory, surreal scenes” rather than literal reality

For example, in Uelsmann’s world “a forest of trees floats high in the sky, roots and all,” or ghostly figures emerge from natural landscapes, or “cupped hands transform into a window overlooking a house in the clouds.”

Such visual poetry has “more in common with Dalí and Magritte” – the giants of Surrealist painting – than with traditional nature photographers like Adams

One of Uelsmann’s iconic motifs is the floating tree, depicted with its roots dangling in mid-air above a mirrored landscape. In this 1970s photomontage, a massive tree levitates over a calm lake, its reflection seamlessly blending into a waterfall-like form below. Uelsmann’s composite images are so well executed that the boundaries between the original components disappear, creating a “seamless and harmonious whole” from many parts

Viewers encountering his work for the first time often react with intrigue and emotion – exactly what the artist intended. “When people see my work, if their first response is ‘how did he do it?’ that’s when I’ve failed,” Uelsmann asserted. “I want the first response to be some authentic emotional response, like ‘gee, that’s weird.’ … I like images that sustain their mystery.”

In service of that mystery, Uelsmann often avoided giving explicit titles to his photographs, preferring them to stand on their own and invite open-ended interpretation. Recurring symbols in his visual vocabulary levitating figures, monumental hands, trees melding into humans or buildings, isolated doorways or eyes weave a symbolic language of dreamlike associations

These elements, drawn from nature, myth and the subconscious, reflect Uelsmann’s interest in what he called “visual myth-making” and give his images an allegorical quality

Despite the often bizarre combinations (disembodied body parts, animals blended with landscapes, etc.), the photos maintain an internal logic and balance that make them compelling artworks rather than mere novelties. Uelsmann’s imaginative vision consistently subverts the viewer’s expectations of what a photograph should look like, proving that the camera could be used to create scenes “emotionally more real than the factual world”

Working Methods in the Darkroom

All of Uelsmann’s surreal effects were achieved entirely with analog darkroom techniques, a feat that astonished his contemporaries and still impresses viewers today. He did not rely on multiple exposures in-camera; rather, he perfected a method of combination printing using multiple enlargers, which allowed him to blend parts of many negatives into a single image. Uelsmann famously maintained a darkroom equipped with up to seven or eight enlargers so that he could work on complex composites efficiently

His breakthrough realization was that by placing different negatives in separate enlargers, he could move the photo paper from one projection to another, layering exposures without having to constantly swap negatives in and out of a single enlarger

This approach dramatically expanded his “explorations and options” in building images

Each enlarger would project a component of the final scene for instance, one might hold a negative of a sky with clouds, another a figure or tree, another a textured background and Uelsmann would expose the photographic paper to each in turn, masking and dodging as needed to control the overlaps

The process required extraordinary patience and skill in burning, dodging, and masking different sections of the paper so that the final print showed a seamless blend

Uelsmann’s darkroom skills were so refined that his composites show no obvious edges or cut lines; the tonal values and lighting of each element are harmonized to appear as one believable (if fantastical) scene. As one reviewer noted, he combined “light, chemistry and the base metal of silver to conjure marvelous dreamscapes” in the darkroom, truly earning the moniker of a “darkroom alchemist.”

Crucially, Uelsmann approached the darkroom as a place of creative discovery rather than mere technical processing. He referred to it as his “visual research lab” where the artistic process could continue after the film was shot

This philosophy ran counter to the dominant doctrine of pre-visualization championed by figures like Ansel Adams, which held that a photographer should conceive the final image fully in mind before taking the picture. Uelsmann instead practiced what he dubbed “post-visualization,” meaning he allowed the image to evolve during printing, often improvising and changing course as new combinations suggested themselves

“The contemporary artist, in all other areas, is no longer restricted to the traditional use of his materials… he is not bound to a fully conceived, pre-visioned end,” Uelsmann argued, encouraging photographers to “re-visualize an image at any point in the photographic process”

In his darkroom sessions (which he likened to a painter’s studio time), Uelsmann would “spend long periods… conducting experiments,” shuffling through his archive of negatives to see what new juxtapositions might spark “something cohesive”

He often went out with his camera to **“collect” images of interesting objects, skies, textures, or locations, with the intention of later isolating and combining them with others in the darkroom

This meant that even the act of photographing was, for him, gathering raw materials for a montage rather than capturing a final composition. Uelsmann described the camera itself as “a license to explore” – a tool that gave him permission to roam and observe the world, harvesting visual elements that he might turn into something magical back in the darkroom

Because of this process, Uelsmann’s workflow was highly iterative and intuitive. He might start with a vague idea or just a compelling pair of images and then ask “what would happen if…?” as he tried different combinations

He called this an “in-process discovery”, where sometimes a trite idea could evolve into something profound only through the act of making and experimenting

Many of his most striking montages were born from this “leap of faith” in the darkroom trusting that disparate negatives could merge to create an unexpected new image

For instance, to produce one 2006 image of hands emerging from a tree trunk holding a bird’s nest, Uelsmann used four enlargers to blend three separate photos: a gnarled tree, his wife’s hands, and a raven perched on cobblestones

He spent days in the darkroom, carefully aligning and exposing these elements until “something magical” came together

He jokingly nicknamed his workspace the “Confluence Room” to signify the merging of visual streams into a single river of imagery

Despite the painstaking nature of his technique, Uelsmann relished the process. “It’s such a rewarding experience to produce personal imagery and have this kind of visual myth emerge over time,” he said of his darkroom work

He remained dedicated to these analog methods even as digital technology became prevalent. “Let us not delude ourselves by the seemingly scientific nature of the darkroom ritual,” Uelsmann remarked; “it has been and always will be a form of alchemy.”

In short, Uelsmann’s working method was a unique fusion of technical virtuosity and imaginative play, yielding photographs that continue to mystify viewers and inspire photographers.

Photographic Philosophy and Vision

From the beginning of his career, Uelsmann championed photography as an expressive, artistic medium – a way to visualize inner realities rather than just record the outer world. In the mid-20th century, this was a bold stance. He came of age in a period when “straight” photography and documentary realism were highly esteemed, but he “joyfully challenged and expanded traditional notions” of what photography could be

Uelsmann believed that the “mind sees more than the eye knows”, and that a photographer could reveal hidden truths or emotions by manipulating images

He viewed his own work as “allegorical surrealist imagery of the unfathomable”, aligning himself with the Surrealist tradition of using fantasy to challenge reality

This outlook was influenced not only by his formal art history studies (which introduced him to Surrealism), but also by mentors like Minor White who taught the importance of conveying inner states and emotions through photographs

Uelsmann often cited his intrigue with artists such as Max Ernst and Joseph Cornell, whose works used fantasy and collage to upend viewers’ perceptions

Like those artists, Uelsmann sought to create images that operate on a psychological or spiritual level. “I see my photography as a spiritual activity,” he said in one interview. “It is a personal quest that permits me to challenge accepted ways of seeing our world.”

He approached image-making almost as a ritual: working regularly in the darkroom with a “sense of ritual involved,” open to whatever revelations might occur through the creative process

Central to Uelsmann’s philosophy was the idea that art should come from within and remain open to interpretation. He often spoke of the 20th-century shift from outward-looking art to inward-looking art, and he felt photography needed to fully partake in this “liberation” of the artist’s imagination

By embracing post-visualization and in-process discovery, Uelsmann was asserting that a photograph need not be predetermined by reality, but could be created much like a painting or poem, guided by intuition and feeling. “The better images occur when you’re moving to the fringes of your own understanding,” he noted, “when you trust what’s happening at a non-intellectual, subconscious level.”

This willingness to venture into the unknown gave his work an improvisational, almost jazz-like character – he balanced control with spontaneity. Uelsmann also acknowledged that altered photographs inevitably raise questions about fact vs. fiction, a tension he embraced. Early in his career, some critics told him “that’s interesting but it isn’t photography” because he was altering the camera’s image

Such comments didn’t deter him; instead, they confirmed that he was “challeng[ing] the limits” and blurring the boundary between reality and imagination in a productive way

As he pointed out, “An Ansel Adams picture of Yosemite is not what you experience when you go there. There is always a transition that breaks from reality”

in other words, all photographs involve some level of interpretation and artifice. Uelsmann simply pushed that idea to an extreme, making the viewer confront how photography can invent new realities rather than just mirror the world.

Despite the complex, often dark imagery he produced, Uelsmann did not impose singular meanings on his work. He preferred that each person bring their own imagination to the viewing. “I allow the viewers to assign any meaning to my work that they wish,” he explained, believing that “there is no one right answer” in art

This open-ended quality is a hallmark of his photographs – they provoke questions and feelings that might differ for each viewer. In fact, Uelsmann found that people sometimes assumed his composite scenes were real at first glance (for example, he would get inquiries asking where he had photographed a particular impossible scene)

The ambiguity and momentary confusion are intentional: his images invite you into a visual riddle or poem. In Uelsmann’s view, photography was fully capable of conveying myths, dreams, and subconscious ideas just as literature or painting could. He often described his images as visual myths or metaphors, and himself as a “visual poet” constructing those myths

By combining classical darkroom craft with a boundless imagination, Uelsmann asserted the legitimacy of photography as a fully expressive art form one that need not stick to straight depiction, but could venture into the surreal and psychological. His philosophy championed creativity and personal vision above all: “Art,” he insisted, “has no singular truth or beauty – its truth, beauty, and even frustration lie in the fact that there is no single correct answer.”

This ethos encouraged not only his own work, but also how he taught photography to students: by urging them to explore a wide range of approaches and to “get beyond the obvious to the next level.”\

Influence on Other Artists

Jerry Uelsmann’s impact on the world of photography and visual arts has been profound. As a pioneer of photomontage in the late 20th century, he paved the way for both his contemporaries and future generations to experiment with merging images and pushing the boundaries of the medium. “His work influenced generations of both analog and digital photographers,” notes one retrospective summary

Indeed, Uelsmann is often cited as a spiritual forefather of the digital compositing revolution. He was assembling fantastical images in the darkroom decades before software like Adobe Photoshop made such montages relatively easy

When the first version of Photoshop was introduced in 1990, Uelsmann’s example loomed large – so much so that Adobe’s creative director invited him in 1995 to collaborate on the launch poster for Photoshop, recognizing that Uelsmann’s analog work “anticipated the capabilities” of digital image-editing

In the eyes of many, he had earned the nickname “Godfather of Photoshop” for demonstrating what was possible in photo-manipulation long before computers

Uelsmann, however, remained humble about this influence and personally chose to stick with the darkroom over digital tools. (At age 83 he quipped that he was too set in his ways to take up Photoshop – “the manuals are insane”, he laughed, though he respected it as another valid tool for artists

Within fine art photography, Uelsmann’s success helped legitimize photomontage and other experimental techniques. In the 1960s, he and a handful of others (such as Duane Michals, who used staged scenes and multiple exposures, and Robert Heinecken, who employed collage and appropriation) showed that photography could be as fluid and inventive as painting or sculpture. This influence is evident in the loosening of rigid norms in photography curricula and exhibitions in subsequent decades. As historian John Szarkowski noted, Uelsmann’s method harked back to Victorian combination printing but was “unmistakably contemporary” in its “surrealistic and ambiguous imagery,” heralding a break from the old rules

By the 1970s and 80s, the field of art photography had expanded to embrace staged, manipulated, and conceptual works – a shift that Uelsmann’s early breakthroughs helped trigger

He was aware, however, that history’s attention can be selective; later in life he observed that mainstream photo history tended to highlight the documentary photographers of his era more than the experimentalists. Yet, whether or not he was always in the limelight, his fingerprints are on countless subsequent works of imaginative photography.

Several artists have drawn direct inspiration from Uelsmann’s imagery and techniques. Notably, Maggie Taylor, a contemporary photographic artist who was also Uelsmann’s third wife, adopted his compositional approach but translated it into the digital realm. As an undergraduate philosophy student turned artist, Taylor was inspired by Uelsmann’s creative freedom and began using flatbed scanners and Photoshop to create her own surreal montages in color

After observing Uelsmann’s reluctance to go digital, Taylor “became intrigued with the many and varied possibilities” of image software and effectively picked up the baton, crafting whimsical dreamscapes with dozens (sometimes hundreds) of layers in a single composition

Her works – often featuring Victorian-era portraits and fantastical elements – are a testament to Uelsmann’s influence, showing how his visual language could be reinterpreted with new technology. Beyond Taylor, one can see Uelsmann’s legacy in the rise of fine art photographers who produce surreal narratives and composite realities: artists who “experiment with new techniques” in photomontage have frequently cited Uelsmann as an inspiration

His name often comes up in the context of contemporary composite photography and photo illustration, from gallery artists to students learning to merge images in creative ways. In effect, Uelsmann opened the floodgates for treating the photograph as malleable clay in the artist’s hands. Today’s digital collage artists and photo-manipulators, whether they know it or not, owe a debt to the trail Uelsmann blazed with his laborious darkroom montages.

Uelsmann’s influence also extends to how photography is taught and discussed. As a longtime professor, he mentored students to think outside the conventional confines of the camera image. His emphasis on “post-visualization” and on photography as a flexible art form encouraged young photographers to consider the medium’s expressive possibilities rather than seeing a photograph as an end in itself

Additionally, major museums and institutions recognized his contribution: MoMA’s 1967 exhibition of Uelsmann’s work was a landmark moment that signaled institutional acceptance of experimental photography

Since then, Uelsmann’s prints have entered the permanent collections of the world’s top museums, and he has been honored with awards (from a Guggenheim Fellowship to a Royal Photographic Society fellowship) celebrating his creativity

This institutional recognition helped validate photomontage as a respected art practice, influencing curators and critics to give serious consideration to manipulated imagery.

In summary, Jerry Uelsmann’s legacy is visible both in the art itself – the countless surreal photographs and digital composites that echo his visual DNA – and in the broader acceptance of photography as a medium of imagination. He showed that the “decisive moment” of clicking the shutter could be just the beginning of a creative journey. Through his dark, surreal visions, Uelsmann expanded the vocabulary of photography and inspired others to “create meaningful images that resonate with audiences” by any means necessary

Whether in a darkroom or on a computer, the spirit of Uelsmann’s work lives on in all artists who believe a photograph can transcend reality and reveal the depths of the human imagination.