Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Historical Origins of Arte Povera

• 2.1. The Post-War Italian Landscape

• 2.2. Socio-Political Context and the 1960s

• 2.3. The Rise of Alternative Art Movements

3. The Roots of Arte Povera

• 3.1. Origins in Minimalism and Conceptual Art

• 3.2. Influence of Dadaism and Surrealism

• 3.3. The Italian Context: Political and Economic Turmoil

4. The Genesis of Arte Povera (1967–1970s)

• 4.1. Germano Celant and the Manifesto

• 4.2. Key Philosophical Underpinnings

• 4.3. Core Artists and Works

5. Materiality and Process: Core Characteristics of Arte Povera

• 5.1. Rejection of Traditional Art Forms

• 5.2. Exploration of Everyday and “Poor” Materials

• 5.3. The Role of the Viewer and Interactive Art

6. Key Figures in Arte Povera

• 6.1. Michelangelo Pistoletto

• 6.2. Giuseppe Penone

• 6.3. Mario Merz

• 6.4. Jannis Kounellis

• 6.5. Alighiero Boetti

7. Related Figures and Supporters

• 7.1. Art Critics and Theorists

• 7.1.1. Germano Celant

• 7.1.2. Rosalind Krauss

• 7.2. Artists Associated with Arte Povera

• 7.2.1. Luciano Fabro

• 7.2.2. Pier Paolo Calzolari

• 7.2.3. Tommaso Cascella

8. Theoretical Influences and Philosophical Foundations

• 8.1. Critique of Capitalism and Consumerism

• 8.2. Engagement with Phenomenology and Existentialism

• 8.2.1. The Existentialist Influence

• 8.2.2. Arte Povera as a Search for Authenticity

• 8.3. Political Context and Resistance

9. Arte Povera’s Impact and Legacy

• 9.1. Influence on Contemporary Art Movements

• 9.2. Environmental and Ecological Art

• 9.3. Conceptual and Installation Art

10. Critical Reception and Controversy

• 10.1. Early Reception of Arte Povera

• 10.2. Criticisms and Misunderstandings of the Movement

• 10.3. Arte Povera’s Enduring Cultural Relevance

11. Arte Povera in the Global Context

• 11.1. Influence of Arte Povera Beyond Italy

• 11.2. The Movement’s Impact on International Contemporary Art

• 11.3. Arte Povera’s Influence on Global Environmental and Eco-Art Practices

12. Conclusion

13. References

1. Introduction

Arte Povera, meaning “poor art” in Italian, emerged as a revolutionary movement in the late 1960s, challenging traditional notions of art, its materials, and its social relevance. This avant-garde movement, founded by a group of Italian artists, sought to break away from the dominance of formalism, high art, and commercialized culture by incorporating everyday, often discarded materials into their works. These raw materials, referred to as “poor materials,” were used to engage directly with the viewer, urging them to reconsider the essence of art, the relationship between art and society, and the role of the artist.

This exploration into Arte Povera’s origins, development, and enduring influence is crucial for understanding how it reshaped contemporary art and why its core themes, such as the critique of consumerism, the rejection of capitalist systems, and the focus on authenticity, continue to resonate today. In this page we will explore the movement’s historical context, the key figures involved, the philosophical underpinnings, and its legacy in contemporary art and society.

2. Historical Origins of Arte Povera

Arte Povera did not emerge in a vacuum; it was deeply influenced by both the political landscape of post war Italy and the broader socio cultural movements of the 1960s. The movement can be understood as a direct response to the increasing commodification of art and the post industrial revolution, where the mechanization and commercialization of society were rapidly changing the cultural fabric. Let us explore these critical factors that laid the foundation for Arte Povera.

2.1. The Post-War Italian Landscape

The aftermath of World War II left Italy in a state of social, political, and economic instability. The country was struggling to recover from the devastation of the war, and the tension between the old and new ways of life was palpable. This period of turmoil created fertile ground for intellectual movements that sought to reimagine society, culture, and art.

The 1960s in Italy were marked by significant political activism and social upheaval. The Italian economic miracle, which brought about rapid industrialization, was accompanied by rising inequality, labor unrest, and growing dissatisfaction with the political establishment. In this charged environment, artists and intellectuals began to question the role of art in society, particularly its relationship to capitalist systems of production and consumption.

Socialist and communist movements gained momentum during this period, with the Italian Communist Party (PCI) experiencing significant growth. The PCI, advocating for economic equality and social justice, found support among workers, peasants, and the lower classes. As a major opposition party, it sought to challenge the capitalist system and expand its influence through democratic and legal means, aligning with broader socialist ideals of economic and political change.

2.2. Socio-Political Context and the 1960s

The 1960s in Italy were marked by significant political activism and social upheaval. The Italian economic miracle, which brought about rapid industrialization, was accompanied by rising inequality, labor unrest, and growing dissatisfaction with the political establishment. In this charged environment, artists and intellectuals began to question the role of art in society, particularly its relationship to capitalist systems of production and consumption. The Italian Communist Party (PCI) experienced significant growth during this time, gaining support from workers, peasants, and the lower classes. The PCI emphasized economic equality and social justice, playing a crucial role in shaping Italy’s social structure. It positioned itself as a major opposition party within Italian politics, seeking to expand its influence through democratic and legal means, while challenging the capitalist status quo.

This period was also characterized by a series of left-wing political movements and protests, including the student riots of 1968 and the wider global movements for social change. In this context, Arte Povera’s rejection of consumerism and traditional art forms mirrored the broader societal call for authenticity, social justice, and resistance against systems of power. Artists began to use their works not just to challenge the status quo but also to question the very role of art in a consumer driven world.

2.3. The Rise of Alternative Art Movements

The 1960s also saw the rise of alternative art movements across the globe, particularly in Europe and North America. These movements, such as Minimalism, Conceptualism, and Fluxus, questioned the boundaries of art and sought to redefine what art could be. Minimalism, for example, focused on simplicity and the use of industrial materials, while Conceptualism emphasized the idea behind the work rather than its material form.

Arte Povera emerged in parallel with these movements but distinguished itself by its deep connection to the local Italian context and its emphasis on raw, organic materials. While it shared some conceptual interests with these other movements, it sought to return art to its material essence, rejecting the sleek and impersonal forms of industrial art. By focusing on the “poor” materials of everyday life, such as soil, stone, metal, and fabric, Arte Povera artists made a radical break with traditional forms of art-making.

3. The Roots of Arte Povera

Arte Povera did not arise in isolation, but was deeply influenced by several key art movements that preceded it. The roots of Arte Povera can be traced back to the minimalistic, conceptual, Dadaist, and surrealist traditions, which all explored similar ideas about the deconstruction of traditional artistic forms and a shift towards more radical, material-based approaches. However, it is crucial to note that Arte Povera emerged specifically in the Italian socio political context of the late 1960s, where it responded directly to the political and economic turmoil of the time.

3.1. Origins in Minimalism and Conceptual Art

“Untitled” 1967, Donald Judd

“monument” for V. Tatlin1964, Dan Flavin

Minimalism and Conceptual Art were significant precursors to the emergence of Arte Povera. Both movements emerged in the late 1950s and 1960s, primarily in the United States, and challenged the traditional conventions of art. Minimalism, led by artists such as Donald Judd and Dan Flavin, focused on the use of industrial materials, geometric shapes, and an emphasis on simplicity. The minimalist approach to art-making stripped away the emotional and representational aspects of art, focusing instead on form and materiality.

Conceptual Art, championed by artists like Sol LeWitt and Joseph Kosuth, shifted the focus of art from the object itself to the idea or concept behind the work. In contrast to traditional notions of art as something tangible and aesthetic, Conceptual Art explored the relationship between language, thought, and visual representation. The artworks were often text-based, with the idea or instruction being the primary medium of expression.

Arte Povera shared the minimalist focus on materiality but deviated from Minimalism in its use of “poor materials.” The raw, unprocessed materials used by Arte Povera artists stood in stark contrast to the industrial materials favored by Minimalism. The rejection of polished, refined objects was an essential component of Arte Povera’s ethos, which aimed to reconnect art with life, nature, and humanity in a direct and immediate way.

In terms of Conceptual Art, Arte Povera artists were also concerned with the idea and the process behind the artwork. However, they placed a stronger emphasis on physicality and materiality, using non-traditional materials to evoke a more visceral, sensory response from the viewer. For example, rather than using text or language to convey concepts, Arte Povera artists often used objects and materials to express ideas that were politically and socially charged, reflecting the tension between the individual and the collective in post-war Italian society.

3.2. Influence of Dadaism and Surrealism

Dadaism and Surrealism, both of which emerged in the early 20th century, had a lasting impact on the development of Arte Povera. Dadaism, with its anti-art stance and its embrace of randomness and absurdity, introduced the idea that anything could be art. Artists like Marcel Duchamp famously challenged traditional definitions of art through the use of found objects, such as his famous “Fountain” (1917), a urinal signed with a pseudonym.

Surrealism, led by figures like Salvador Dalí and André Breton, also had a significant influence on Arte Povera’s use of unconventional materials. Surrealists sought to express the unconscious mind, dreams, and the irrational, often using bizarre juxtapositions and everyday objects in their works. While Arte Povera did not directly draw from Surrealism’s dreamlike qualities, it did adopt a similar approach to everyday objects, using materials in unexpected and provocative ways to break down the boundary between the ordinary and the extraordinary.

The Dadaist focus on anti-art and subversion of traditional artistic norms can be seen in Arte Povera’s rejection of the commercialized, formalized art world. The movement’s use of discarded or “poor” materials challenged the hierarchical distinction between high art and low art, as well as the commercialization of artistic production. Surrealism’s emphasis on the subconscious and the irrational also resonates in Arte Povera’s exploration of materiality and physicality, where the process of creating art becomes a form of expression that goes beyond rationality.

3.3. The Italian Context: Political and Economic Turmoil

The socio-political and economic climate of 1960s Italy was a significant factor in shaping Arte Povera. Following World War II, Italy underwent a process of rapid industrialization and economic growth, known as the Italian Economic Miracle. While this period saw improvements in living standards and the rise of consumer culture, it also generated deep social and political unrest. The burgeoning class divide and the influence of left-wing political movements created a fertile ground for artistic and intellectual challenges to the status quo.

By the late 1960s, Italy was experiencing widespread political and social upheaval. The student protests of 1968, labor strikes, and a rising dissatisfaction with capitalist systems fueled a sense of rebellion and resistance among artists. Arte Povera emerged as a response to this turbulence, with its emphasis on the rejection of consumerism, the critique of capitalism, and the focus on the materiality of art. The use of “poor” materials reflected a critique of the excesses and artificiality of mass production, echoing the anti-capitalist sentiments prevalent in the broader political context.

Additionally, the political and economic turmoil in Italy was mirrored in the collective consciousness of the artists who embraced Arte Povera. They sought to create art that was not only a reflection of personal expression but also a reaction to the socio-political conditions around them. The works created during this period often contained powerful political undertones, critiquing industrialization, the dehumanizing effects of modern technology, and the erosion of traditional cultural values in the face of consumer capitalism.

4. The Genesis of Arte Povera (1967–1970s)

The origins of Arte Povera can be traced to the late 1960s, particularly with its formalization in 1967 as a response to both the political and cultural upheavals of the time. The movement emerged at a moment of social and economic tension, and it sought to redefine the nature of art by rejecting traditional media and embracing raw, often humble materials. The birth of Arte Povera was not merely an artistic rebellion; it reflected a deeper philosophical engagement with the nature of life, materiality, and society in a period of transformation.

4.1. Germano Celant and the Manifesto

The movement’s name, “Arte Povera,” was coined by art critic Germano Celant in 1967. In his manifesto, Celant declared that art should be rooted in life itself, using materials and forms that were unpretentious and simple. The manifesto emphasized that the use of “poor” materials was not just an aesthetic choice but a philosophical statement—a rejection of the elitism and commercialization of art. Celant’s role as both a critic and theorist helped solidify the movement and its place in the art world.

4.2. Key Philosophical Underpinnings

The philosophical foundations of Arte Povera were deeply intertwined with existentialism. The movement was a direct response to the sense of alienation, disillusionment, and search for meaning that characterized much of the 20th century. The use of raw, often discarded materials served as a metaphor for the human condition—imperfect, fragile, and always in the process of becoming. The existentialist notion of individual freedom, the absurdity of existence, and the rejection of societal norms were central to the artists’ approach.

4.3. Core Artists and Works

Some of the key artists of the movement included Michelangelo Pistoletto, Mario Merz, and Jannis Kounellis, Giovanni Anselmo, Alighiero Boetti, Pier Paolo Calzolari, Luciano Fabro, Piero Gilardi, Jannis Kounellis, Marisa Merz, Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascali, Giuseppe Penone, Emilio Prini and Gilberto Zorio whose works challenged traditional notions of art.

Pistoletto’s reflective surfaces, for example, invited the viewer to become a part of the artwork itself, blurring the boundaries between subject and object. Merz’s use of neon lights and organic materials created dynamic, ever-changing installations that embodied the flux and uncertainty of life. Kounellis, known for his installations involving live animals, also explored the relationship between humanity and nature, often blurring the lines between life and art.

5. Materiality and Process: Core Characteristics of Arte Povera

Arte Povera’s defining characteristic lies in its exploration of materiality and process, which allowed artists to move beyond traditional methods of artistic expression. This movement was deeply concerned with the relationship between materials, human labor, and the environment. The artists of Arte Povera rejected the polished, finished artworks of classical tradition, instead embracing a more elemental, raw approach to art-making. This focus on poor materials such as wood, metal, earth, fabric, and even live animals—became central to the movement, reflecting a desire to break free from the constraints of both the art market and the formalities of high art.

5.1. Rejection of Traditional Art Forms

One of the key principles of Arte Povera was the rejection of traditional artistic media and techniques. Artists moved away from painting, sculpture, and other conventional forms of art and explored new ways of using materials and creating works. The movement’s aim was to erase the boundaries that had defined art, creating a more direct and authentic engagement with materials. This rejection of the established art canon allowed for a more experimental, open-ended approach to creation, which emphasized the physical properties of materials and the process of making art itself.

By abandoning the traditional notion of a “finished” artwork, Arte Povera introduced the idea that art could be a process rather than a static object. Works of art were often created in direct response to their environments, changing as the materials aged, decayed, or interacted with the surroundings. This was an active critique of the traditional role of the artist as a creator of fixed, final objects, instead positioning them as participants in an ongoing dialogue with the materials and the viewer.

5.2. Exploration of Everyday and “Poor” Materials

The exploration of “poor” materials is arguably the most iconic aspect of Arte Povera. These materials—such as stones, glass, metal, wood, fabric, and even organic matter like plants and animals—were chosen not for their beauty or cultural status but for their inherent rawness and authenticity. By using these materials, the artists aimed to strip away the artifice associated with traditional mediums like oil paint or marble, grounding their works in the natural world and the realities of everyday life.

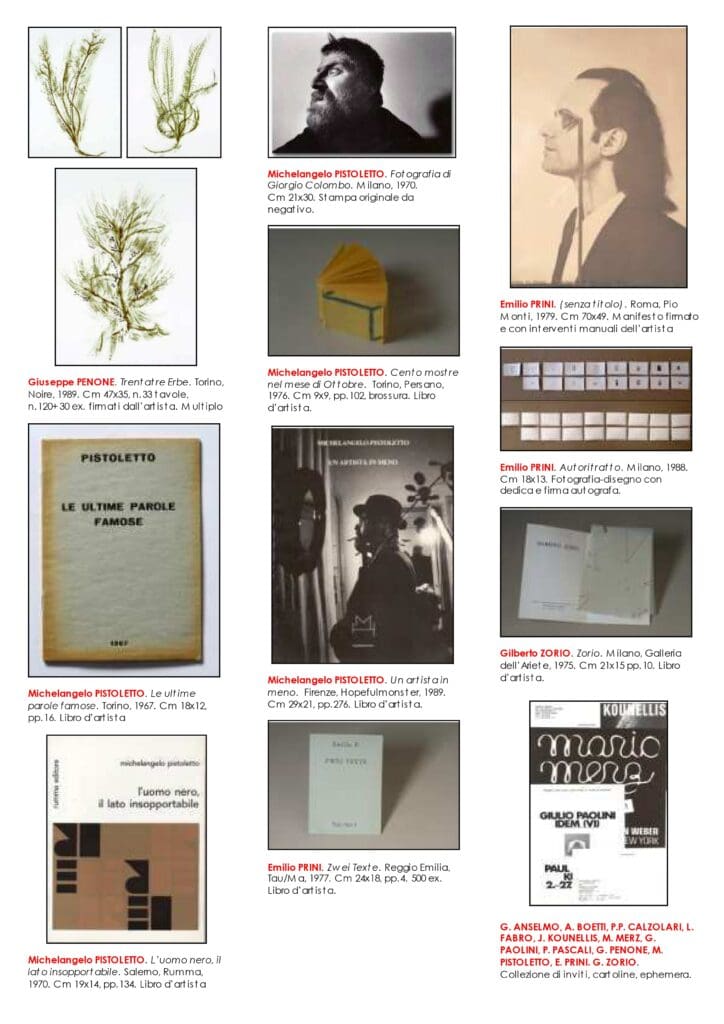

These materials were often altered or manipulated in ways that encouraged viewers to consider the inherent properties of the objects and the processes of transformation they underwent. For instance, artists like Giuseppe Penone worked with trees and wood, using these organic materials to explore the connection between the natural world and human intervention. Similarly, Mario Merz utilized materials like neon light and stone to evoke themes of survival and time. These works often appeared unpolished, as though they had just emerged from the natural world, reflecting Arte Povera’s commitment to authenticity and raw expression.

5.3. The Role of the Viewer and Interactive Art

Arte Povera sought to dissolve the traditional barrier between the artwork and the viewer. The role of the viewer became crucial, as artists intentionally created works that invited direct interaction, both physically and intellectually. Rather than simply observing the artwork from a distance, the viewer was encouraged to engage with the materials, whether through movement, touch, or interpretation. This interactivity aimed to foster a deeper connection between the viewer and the artwork, allowing the viewer to become an active participant in the creation and meaning-making process.

Some works, like Michelangelo Pistoletto’s mirror pieces, reflected the viewer’s image, forcing them to confront themselves as part of the artwork. In other pieces, like Jannis Kounellis’s installations with live animals, the viewer became part of the living environment of the artwork, blurring the lines between art and life. These works emphasized the notion that art is not just something to be looked at, but something to be experienced, lived with, and actively engaged.

In conclusion, Arte Povera’s focus on materiality and process represents a radical departure from traditional art practices. By embracing everyday, “poor” materials and redefining the role of the viewer, the movement emphasized the importance of direct engagement with the physical world, inviting the viewer to participate in the creation and meaning of the work. Through this, Arte Povera opened up new possibilities for how art could be conceived, made, and experienced, leaving a lasting legacy that continues to influence contemporary art today.

6. Key Figures in Arte Povera

Arte Povera is defined by the works and visions of its central artists, who embraced the movement’s rejection of traditional media and its emphasis on the rawness of materials. These key figures not only pioneered the aesthetic principles of Arte Povera but also helped shape the movement’s philosophical and conceptual foundations. Their artworks challenged conventional notions of beauty, authorship, and materiality, and they were instrumental in pushing the boundaries of what art could be.

6.1. Michelangelo Pistoletto

Michelangelo Pistoletto is one of the most influential figures in Arte Povera, known for his innovative use of mirrors as a central element in his work. Pistoletto’s Mirror Paintings are iconic examples of how the artist engaged the viewer directly in the artwork. By painting on reflective surfaces, Pistoletto created a dynamic interaction between the viewer and the art itself, positioning the viewer as an active participant in the artwork.

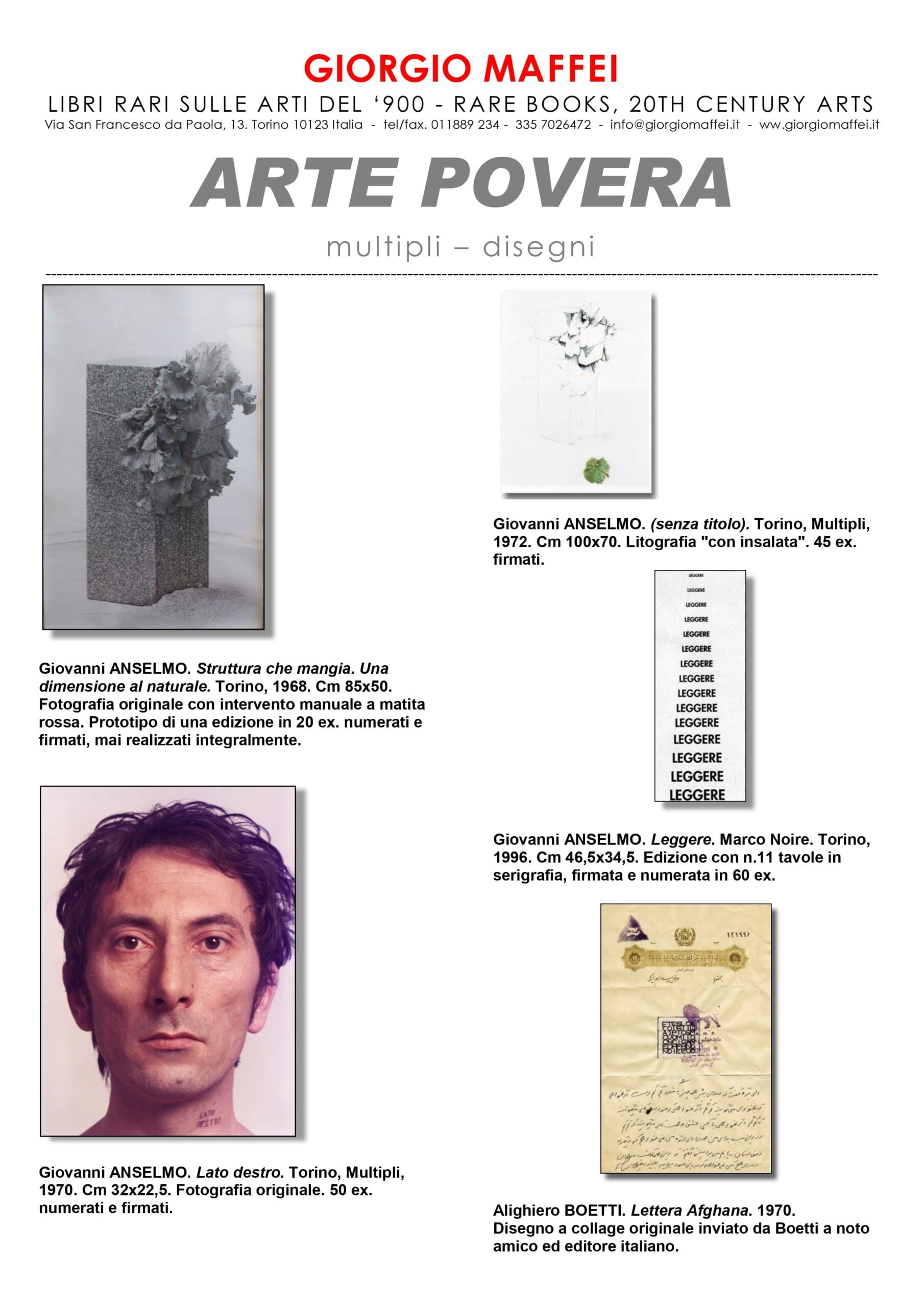

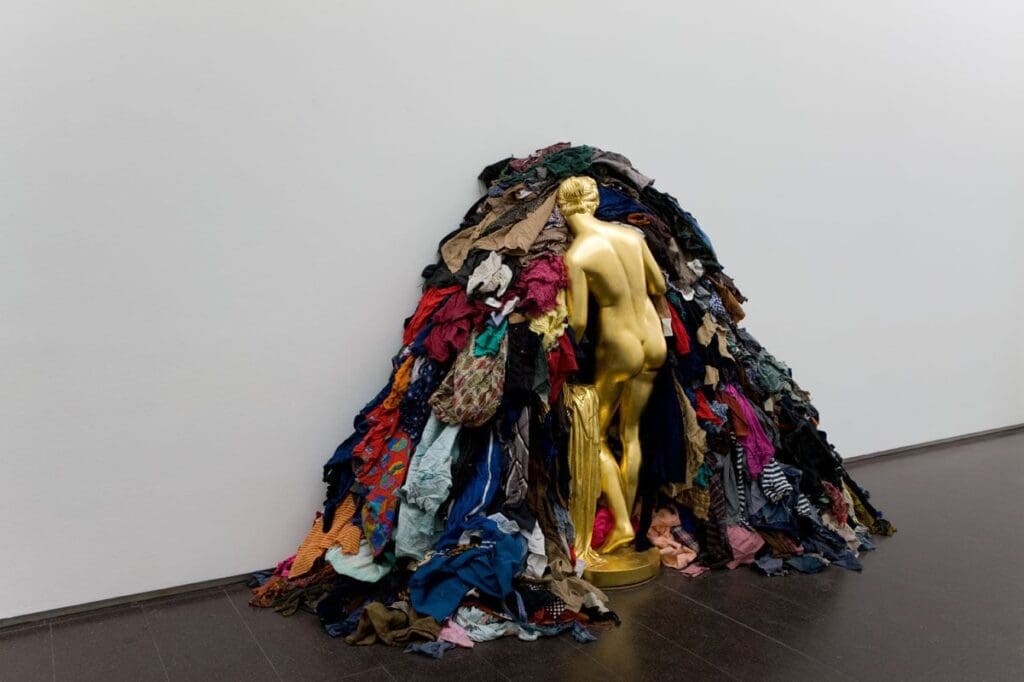

His famous work, “Venus of the Rags” (1967), exemplifies Pistoletto’s approach to Arte Povera. The piece features a classical statue of Venus surrounded by piles of colorful rags. This juxtaposition of high art and “poor” materials is a direct challenge to the traditional notions of artistic beauty and value. Pistoletto’s focus on the relationship between the viewer and the artwork, along with his use of everyday objects, solidified his role as one of the most important figures in the movement.

6.2. Giuseppe Penone

Giuseppe Penone is another central artist in the Arte Povera movement, known for his deep engagement with nature and the human body. Penone’s work often explores themes of time, transformation, and the interaction between humans and the natural world. His use of materials such as trees, stones, and organic matter reflects the movement’s emphasis on raw, elemental materials.

One of Penone’s most iconic works is “Continuerà a crescere tranne che in quel punto” (1968), where he used a human handprint to mark the bark of a tree. This work explores the relationship between human presence and natural growth, suggesting a profound connection between humans and the environment. Penone’s work consistently engages with the idea of nature as both a material and a metaphor for broader existential themes, contributing significantly to Arte Povera’s philosophical underpinnings.

6.3. Mario Merz

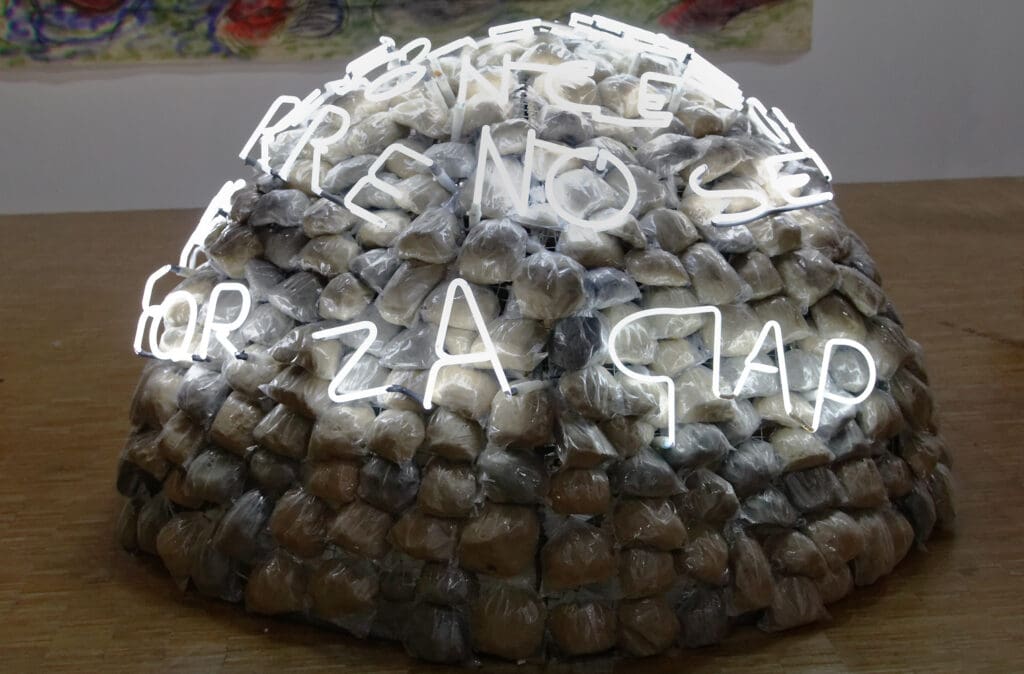

Mario Merz was another key figure in Arte Povera, best known for his use of neon lights, stone, and fiberglass, which he employed to create works that blend conceptual art with natural forms. Merz’s work often explored themes of survival, time, and the relationship between human beings and nature. He famously used igloos in his installations, a symbol of both primitive shelter and a larger philosophical reflection on survival and human existence.

Merz’s “Igloo di Giap” (1968), one of his most famous works, combines the concept of shelter with neon lighting, creating a piece that evokes ideas of survival and isolation. His integration of light and organic materials made his works poetic and philosophical, imbuing them with both a physical presence and a metaphysical weight.

6.4. Jannis Kounellis

Jannis Kounellis was a Greek-Italian artist whose works often involved live animals, fire, and other unpredictable materials that interacted with the viewer and the space in profound ways. Kounellis used performance and installations to explore themes of life, death, and the human experience in a raw and immediate way. His use of animals, such as horses in his early works, highlighted the dynamic interaction between organic life and art, further breaking down the barriers between art and life.

In works like “12 Horses” (1969), Kounellis placed live horses in a gallery space, tying the work directly to the environment and its viewers. This piece embodied the conceptual radicalism of Arte Povera, using non-traditional materials to express powerful emotional and philosophical messages. His work continuously questioned the boundaries of art, insisting that art should confront its audience with the realities of life and the rawness of existence.

6.5. Alighiero Boetti

Alighiero Boetti’s contribution to Arte Povera is particularly significant in the realm of conceptual art. Known for his complex, often politically charged works, Boetti explored the concept of order and chaos in his art. His works were often made using simple materials such as thread, paper, and fabric, and they frequently involved intricate patterns and systems that blurred the lines between order and disorder.

One of his best-known series, “Mappa” (1971-1994), consisted of embroidered world maps that depicted the political boundaries of countries at different points in time. These maps reflected his interest in global politics, change, and interconnectivity. Boetti’s engagement with materials and his exploration of the relationship between intellect and craft made him an important figure in the Arte Povera movement, emphasizing the intellectual and political potential of seemingly mundane objects and processes.

7. Related Figures and Supporters

The success and development of Arte Povera were not only driven by the core group of artists but also by a number of critics, theorists, and additional artists who contributed to shaping the movement’s direction and dissemination. These figures were integral in supporting, interpreting, and expanding the ideas that defined Arte Povera, both within Italy and internationally.

7.1. Art Critics and Theorists

Critics and theorists played a crucial role in the conceptual development and promotion of Arte Povera, providing intellectual frameworks that supported the movement’s principles. Among the most influential of these figures was Germano Celant, the movement’s most prominent advocate, along with Rosalind Krauss, whose theoretical work helped to contextualize the broader impact of Arte Povera.

7.1.1. Germano Celant

Germano Celant, an Italian art historian and curator, is often credited with coining the term “Arte Povera” and defining its core ideas. Celant first used the term in 1967 to describe the experimental and material-based works of a group of Italian artists who rejected the commercialized and institutionalized forms of art. His theoretical writings, particularly the “Arte Povera” manifesto, became foundational for understanding the movement’s rejection of traditional aesthetics and its emphasis on the materiality of art.

Celant’s promotion of Arte Povera went beyond mere criticism; he was actively involved in organizing exhibitions and advocating for the movement’s significance within the broader international art scene. His work continues to be essential for anyone studying Arte Povera and its lasting influence on contemporary art.

7.1.2. Rosalind Krauss

Rosalind Krauss, an American art critic and theorist, also made significant contributions to the intellectual foundations of Arte Povera. Though she was not directly involved with the movement, Krauss’s writings on minimalism and conceptual art helped situate Arte Povera within the broader context of the post-war avant-garde. Krauss’s analysis of the relationship between art, material, and space offered an insightful framework for understanding how the movement’s rejection of traditional art forms could be seen as part of a larger questioning of the nature of artistic representation and the role of the viewer.

Her work, especially in her book “Passages in Modern Sculpture”, connected Arte Povera to international trends in conceptual and minimal art, helping critics and scholars understand the movement’s significance outside of Italy.

7.2. Artists Associated with Arte Povera

Beyond the core figures of Arte Povera, there were several other artists who were closely associated with the movement, contributing to its development or engaging with its themes. These artists shared a similar focus on the use of everyday materials and the exploration of new forms of artistic expression.

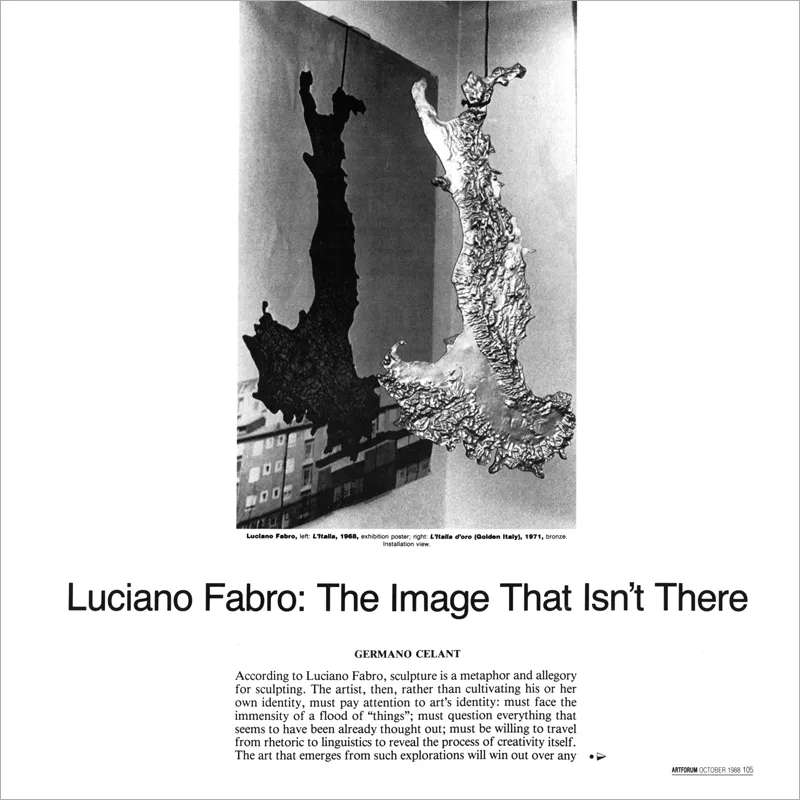

7.2.1. Luciano Fabro

Luciano Fabro was an artist whose work was closely tied to the principles of Arte Povera. Known for his use of natural materials, Fabro often incorporated stone, metal, and fabric into his sculptures and installations. His works explore themes of identity, language, and the physicality of objects, making him a key figure in the movement’s philosophical development.

One of Fabro’s notable works, “Italy” (1968), was a map of Italy made from jute, a humble material that reflected his interest in the symbolism of geography and territory. Fabro’s art was deeply rooted in the human condition, drawing connections between material and meaning. His unique contribution to Arte Povera lies in his ability to integrate conceptual rigor with material exploration.

7.2.2. Pier Paolo Calzolari

Pier Paolo Calzolari was another important figure within Arte Povera, known for his use of unconventional materials such as salt, fire, and lead. Calzolari’s works often involved natural processes, like corrosion and transformation, emphasizing the impermanence of life and the passage of time. His works were often experimental and interactive, making them highly engaging and dynamic.

In Senza titolo (1969), Pier Paolo Calzolari used simple materials like sulfur, salt, and metal to create an evolving installation that responded to the environment. The piece engaged the viewer in a sensory experience, as the materials changed over time, reflecting themes of decay and transformation. The work emphasized impermanence and the passage of time, aligning with the principles of Arte Povera, which focused on using raw, everyday materials to express the natural and transient qualities of the world around us.

7.2.3. Tommaso Cascella

Tommaso Cascella, an Italian sculptor, worked in a style that aligned with Arte Povera’s focus on natural materials and organic forms. He often used stone and wood to create sculptures that referenced both the human body and the natural world. Cascella’s works were a direct response to the geopolitical and social climate of the time, and they reflected the fragility of human existence, often evoking themes of mortality and transience.

8. Theoretical Influences and Philosophical Foundations

Arte Povera was deeply rooted in various philosophical and theoretical frameworks, which guided its rejection of traditional art forms and its focus on materiality and the process of creation. The movement’s intellectual foundations were shaped by critiques of the contemporary world, particularly in relation to capitalism, consumerism, and the alienation of the individual. Furthermore, the influence of phenomenology and existentialism provided a philosophical backdrop for many of the movement’s central themes, as artists sought to create works that resonated with the authenticity of experience and the fundamental nature of being. The political context of the 1960s and 1970s, marked by social upheaval and resistance, also played a crucial role in shaping the ethos of Arte Povera.

8.1. Critique of Capitalism and Consumerism

One of the foundational aspects of Arte Povera was its critique of capitalism and the increasingly commodified world of art. The movement emerged during a time when consumer culture was on the rise, particularly in Italy, and artists sought to resist the idea of art as a commodity. Arte Povera, by using humble, everyday materials, rejected the notion that art should be tied to market value or commercial interests.

This critique was part of a broader anti-establishment sentiment that permeated the 1960s, as artists and intellectuals began to question the ethics and impact of consumerism on culture, identity, and the environment. In rejecting conventional materials like canvas and oil paint, Arte Povera artists sought to disrupt the hierarchy of art materials that had been established by the art market, thus challenging the commodification of art itself.

By incorporating found materials such as wood, metal, and stone, Arte Povera not only questioned the traditional notion of artistic value but also emphasized the material presence of objects as a form of resistance against the consumer-driven culture. The movement’s emphasis on impermanence and rawness also served as a reminder of the ephemeral nature of life, reinforcing its anti-capitalist stance.

8.2. Engagement with Phenomenology and Existentialism

Arte Povera’s deep philosophical roots can be traced to phenomenology and existentialism, two schools of thought that focus on human experience, existence, and the perception of the world.

Phenomenology, particularly as articulated by thinkers like Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, emphasizes the importance of experience and perception in understanding reality. Similarly, existentialism, championed by philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger, examines the individual’s search for meaning and authenticity in a world that often seems alienating and absurd.

8.2.1. The Existentialist Influence

The influence of existentialism is evident in the works of Arte Povera artists, who often focused on themes of human existence, impermanence, and the search for meaning in an increasingly industrialized and mechanized world. For example, the use of raw, unrefined materials in Arte Povera art can be seen as a reflection of the existentialist idea of authenticity, where the artist returns to the essential elements of existence, shunning superficiality and artifice.

Existentialist thinkers, especially Sartre, emphasized the need for individuals to create their own meaning in an indifferent and often hostile world. Similarly, Arte Povera artists sought to strip away the distractions and pretensions of traditional art, allowing the materials themselves to be the focus, thereby engaging in a more direct and authentic expression of their experiences and ideas.

The exhibition at the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco brings together works Pier Paolo Calzolari produced between the late 1960s and 2014. Titled Casa ideale (Ideal Home) after a “text-manifesto” written in 1968, and spread across Villa Paloma’s three floors, the exhibition plays on the codes of interiors, that is to say the codes of the personal that echo the existentialism of the artist’s production.

8.2.2. Arte Povera as a Search for Authenticity

Arte Povera’s exploration of authenticity was grounded in its rejection of artifice and preconceived notions about art. By working with materials that were often viewed as lowly or ordinary, such as dirt, paper, and stone, Arte Povera artists sought to reconnect with a primitive and authentic experience of the world. This emphasis on raw materials reflected the existentialist search for a deeper, more genuine connection to life and existence.

The movement’s embrace of the material and process-based art reflected an anti-illusionist approach that aligned with the existential desire to confront life without pretense. For many Arte Povera artists, the creation of art was an expression of subjective reality, drawing attention to the impermanence and fragility of the materials they used as a way to speak directly to human experience.

8.3. Political Context and Resistance

The political context in which Arte Povera emerged was marked by significant social and political unrest. The 1960s and 1970s were a time of student protests, labor strikes, and political movements in Italy and across Europe. These movements called for social change, greater equality, and a rejection of institutional authority, all of which resonated with the ethos of Arte Povera.

The movement’s emphasis on rejection of tradition and anti-commercialism was, in many ways, a direct response to the political and economic climate of the time. In Italy, where the political left was gaining momentum and the cultural elite were seen as part of the status quo, Arte Povera’s resistance to institutional art and the commercialization of the art market became a form of political protest.

Moreover, Arte Povera’s focus on raw, unrefined materials can be seen as a critique of the technocratic and industrialized world, which was viewed as alienating and dehumanizing. By emphasizing human connection to nature and materiality, Arte Povera artists resisted the over-industrialization of society and the domination of technology over human experience.

In summary, the philosophical underpinnings of Arte Povera are deeply rooted in critiques of capitalism, a quest for authenticity, and the influence of existentialism and phenomenology. The movement’s resistance to commercialized art, its engagement with political contexts, and its focus on raw materials reflect a desire to challenge the conventions of both art and society, making it a revolutionary and highly influential movement in the world of contemporary art.

9. Arte Povera’s Impact and Legacy

Arte Povera, though short-lived as an organized movement, left a profound and lasting influence on the art world, with its legacy continuing to shape contemporary artistic practices. Its radical rejection of traditional artistic materials and conventions not only transformed how art was created but also how it was perceived and understood. The movement’s focus on materiality, process, and viewer interaction pushed boundaries, laying the groundwork for many of the developments in art that followed. The legacy of Arte Povera can be seen in a variety of ways, from its influence on contemporary art movements to its contributions to environmental and ecological art.

9.1. Influence on Contemporary Art Movements

One of Arte Povera’s most significant impacts is its contribution to the development of subsequent art movements, particularly in the realm of conceptual, installation, and environmental art. The movement’s exploration of materials, physicality, and viewer interaction opened the door for artists to engage with new mediums, often questioning traditional notions of what constituted “art.” For example, the use of natural elements, industrial materials, and discarded objects that defined Arte Povera can be seen in the practices of later artists such as Damien Hirst and Richard Long, who incorporate similar themes of impermanence and material transformation.

The legacy of Arte Povera also influenced the conceptual art movement, with its emphasis on process over product. Artists like Joseph Beuys and Lawrence Weiner, who are central figures in conceptualism, shared a similar approach of using materials as part of the artwork’s meaning rather than merely as aesthetic objects. The ideas of fragility, transience, and the questioning of cultural and economic systems found in Arte Povera continue to resonate in contemporary practices.

9.2. Environmental and Ecological Art

Arte Povera’s deep engagement with natural and organic materials also laid the foundation for ecological and environmental art practices. The movement’s use of earth, rocks, and plant life anticipated a growing interest in sustainability and ecological concerns within the art world. Artists working in the tradition of Arte Povera, such as Giuseppe Penone, emphasized the interconnectedness of human beings and nature, making them key figures in the development of environmental art. The dialogue between human activity and nature, central to Arte Povera, has remained a pivotal theme in the environmental and eco-art movements.

The emphasis on the “poor” and the natural in Arte Povera’s material choices has echoed in contemporary art’s ongoing relationship with sustainability. This includes works that address environmental degradation, the use of recycled materials, and the exploration of themes such as waste, sustainability, and the human footprint on the planet. Today, many contemporary artists explore environmental issues using methods inspired by Arte Povera, making the movement’s influence evident in a wide range of art forms focused on nature and its preservation.

9.3. Conceptual and Installation Art

Another major contribution of Arte Povera is its influence on conceptual and installation art. The movement’s departure from traditional sculpture and its emphasis on process-based work paved the way for the rise of installation art, where the environment itself becomes an artwork. The idea that art is not merely an object but an experience that engages the viewer’s perception, body, and environment is a concept that Arte Povera popularized and later fully developed in the broader installation art scene.

This legacy is particularly evident in the works of artists like Olafur Eliasson, who creates large-scale installations that immerse viewers in environments composed of light, sound, and natural materials, much like Arte Povera’s interactive and immersive installations. Additionally, artists such as Anish Kapoor, who create large, site-specific installations, also reflect the movement’s influence, where materiality, space, and the viewer’s interaction with the artwork remain central to the experience.

Legacy in Contemporary Practice

Arte Povera’s legacy is further demonstrated by its continued relevance in contemporary exhibitions and biennials around the world. It has inspired a wide range of art practices across different media, from painting and sculpture to film and digital art. The movement’s emphasis on the visceral and the real — using materials that are raw, unprocessed, or organic — remains an important reference for many contemporary artists who wish to break free from the constraints of commercialism, high art, and consumer culture. In addition, the movement’s critique of capitalist consumerism continues to resonate in a world where materialism and the commodification of culture are increasingly evident.

Arte Povera’s impact is also evident in the way art institutions, galleries, and museums continue to engage with its work and legacy. Exhibitions focusing on the movement and its key figures continue to draw significant interest, while younger generations of artists remain influenced by the movement’s ability to challenge convention and create art that is both radical and deeply human in its exploration of everyday materials.

10. Critical Reception and Controversy

From its inception, Arte Povera provoked a wide range of reactions, from enthusiastic support to vehement criticism. The movement’s innovative use of unconventional materials and its break from traditional artistic norms challenged established perceptions of art and its purpose. The critical reception of Arte Povera was shaped by various factors, including political climate, artistic tradition, and the broader cultural landscape of the 1960s and 1970s.

10.1. Early Reception of Arte Povera

When Arte Povera first emerged in the late 1960s, it was hailed by many as a revolutionary artistic movement that sought to break free from the confines of the art establishment. Pioneered by the critic Germano Celant, the movement was quickly recognized for its bold approach to materiality and its embrace of anti-establishment and anti-consumerist sentiments. In Italy, where the movement was born, it resonated with the socio-political climate of the time, particularly the rising student protests and the broader countercultural movements across Europe.

The early reception of Arte Povera in the international art world was largely positive among avant-garde critics and artists who appreciated its rejection of commercialism and institutional art norms. Celant’s curatorial efforts, particularly in his exhibitions such as “Arte Povera e Im Spazio” (1967), helped position the movement as a significant part of the international avant-garde, with artists like Michelangelo Pistoletto, Mario Merz, and Jannis Kounellis gaining critical acclaim for their challenging works that incorporated humble materials, such as mud, stone, and metal.

However, not everyone embraced the movement immediately. The use of materials that were traditionally considered “poor” was seen by some as a radical gesture that lacked formal rigor. Traditionalists and more conservative art critics dismissed the works as mere “assemblages” or “junk,” not recognizing their deeper philosophical implications. Nevertheless, the movement gained momentum, especially as younger artists and critics were drawn to its rebellious spirit.

10.2. Criticisms and Misunderstandings of the Movement

Despite its early successes, Arte Povera faced significant criticism throughout its development. The most common criticism leveled against the movement was that its use of raw and unrefined materials was superficial and lacked artistic sophistication. Some critics argued that by using industrial materials or detritus, the artists were lowering the standards of what constituted fine art. This view was particularly prevalent among traditional art institutions, galleries, and critics who felt that Arte Povera’s rejection of established forms and its anti-capitalist stance threatened the status quo.

Another critique of the movement was that, while it aimed to challenge the art market and the commercialization of art, it inadvertently became a part of the very system it sought to critique. Many Arte Povera artists found themselves showing in prestigious galleries and museums, which raised questions about the movement’s relationship with institutional power. The irony of Arte Povera’s works becoming commodified or exhibited in highly commercialized contexts was not lost on its critics, who saw this as a contradiction to the movement’s anti-materialistic message.

Moreover, the movement’s emphasis on process and the ephemeral nature of its materials left some spectators and critics puzzled. Unlike traditional works of art, which were created to last and often to be treasured, many Arte Povera pieces were transient, sometimes decaying or disintegrating over time. This aspect of impermanence led some critics to question the value of such works and whether they could be considered “art” at all.

10.3. Arte Povera’s Enduring Cultural Relevance

Despite early criticisms and controversies, Arte Povera’s cultural and artistic impact has endured. Over the decades, the movement has been increasingly understood not only as a reaction to the consumerism and industrialization of the 1960s but also as a prescient commentary on contemporary issues. Its focus on materiality, the use of discarded objects, and its engagement with the environment have positioned it as an influential precursor to later environmental and ecological art movements.

Arte Povera’s anti-capitalist message resonates more than ever in the modern world, where art continues to be commodified, and global consumer culture dominates. The movement’s refusal to adhere to the commercialized art market, coupled with its embrace of humble materials, has inspired numerous contemporary artists to explore alternative modes of expression, often using everyday materials and questioning the role of art in society.

Moreover, the movement’s engagement with existentialist and phenomenological ideas has given it a philosophical depth that continues to influence contemporary thought. The concept of authenticity, personal experience, and the search for meaning through direct engagement with materials resonates with current debates on identity, personal agency, and the human relationship with nature.

In a time when digital technology and virtual spaces increasingly dominate the art world, Arte Povera’s return to the tactile and the physical offers an essential counterpoint. The movement’s continued relevance lies in its ability to speak to a world that remains disillusioned by the excesses of consumerism and disconnected from the material world, making it a timeless and enduring cultural force.

11. Arte Povera in the Global Context

Arte Povera’s reach extended far beyond its birthplace in Italy, influencing not only the Italian art scene but also having a profound impact on the global art community. As the movement gained international recognition, its innovative use of materials, rejection of consumerism, and critique of capitalist ideologies resonated with artists around the world. In the global context, Arte Povera has continued to shape both contemporary art movements and the philosophical underpinnings of art practice.

11.1. Influence of Arte Povera Beyond Italy

While Arte Povera began as a distinctly Italian movement, its radical ideas spread across Europe and into the broader international art world, where they left an indelible mark. The movement’s innovative approach to materiality and its rejection of traditional artistic forms struck a chord with many artists who sought to challenge the conventions of their own cultural contexts. In particular, Arte Povera’s critique of industrialization and consumerism resonated deeply with artists in post-industrial nations, where the impact of globalization and mass production had led to similar concerns about the environment, social inequality, and the human condition.

In the United States, for example, Arte Povera’s influence can be seen in the work of artists associated with the Minimalist and Conceptual art movements. Artists like Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, and Eva Hesse explored similar themes of materiality, impermanence, and process, using raw, industrial materials in ways that mirrored the concerns of Arte Povera artists. The connection between Arte Povera and American Minimalism is particularly evident in the use of non-traditional materials and the focus on the physicality of the artwork. While there were differences in approach, both movements shared a common interest in redefining the role of the artist and the artwork in a rapidly changing world.

Additionally, in Latin America, artists grappling with issues of political oppression, social unrest, and economic inequality found a strong resonance in Arte Povera’s critique of consumer culture and capitalist structures. The use of found materials and the focus on site-specific works aligned with the struggles of artists in regions where resources were often scarce, and the need for socially engaged art was urgent. Arte Povera’s emphasis on the materiality of art provided a platform for artists to critique their own socio-political environments, often using materials that were intimately tied to their local contexts.

11.2. The Movement’s Impact on International Contemporary Art

Arte Povera’s influence on contemporary art can be seen in numerous international movements that emerged after its inception. The ideas of process, materiality, and impermanence have reverberated through various artistic practices, from environmental art to installation and conceptual art. The movement’s emphasis on the importance of direct engagement with materials and its rejection of traditional artistic hierarchies laid the groundwork for later practices that blurred the boundaries between art, activism, and everyday life.

One of the key ways in which Arte Povera has influenced contemporary art is through its legacy of site-specific and installation art. Artists like Christo and Jeanne-Claude, who famously wrapped large-scale structures in fabric, or Anish Kapoor, who used unconventional materials in monumental public sculptures, have continued the legacy of exploring the relationship between art and its environment. Arte Povera’s use of materials that are often found, discarded, or ephemeral is also mirrored in the work of contemporary artists who engage with environmental issues or the transience of human existence.

Furthermore, the movement’s anti-commercial stance has influenced artists who seek to resist the commodification of art. Today, many artists continue to explore non-precious materials and processes in order to challenge the commercial art market and the commodification of creativity. Arte Povera’s critique of the art market remains particularly relevant in a time when art has become increasingly driven by financial speculation and the pursuit of celebrity status.

11.3. Arte Povera’s Influence on Global Environmental and Eco-Art Practices

One of the most significant areas in which Arte Povera’s influence has been felt is in the realm of environmental and eco-art practices. The movement’s engagement with natural materials and its focus on the relationship between art and the environment anticipated the rise of ecological concerns in art. By using materials such as stones, plants, and soil, Arte Povera artists directly engaged with nature and environmental issues long before the widespread recognition of climate change and environmental degradation.

Today, many contemporary artists continue to draw on the principles of Arte Povera to create works that address ecological themes. The use of sustainable materials, recycling, and the exploration of nature’s fragility are common themes in eco-art. Artists like Olafur Eliasson, who creates large-scale environmental installations that engage with climate change, and Agnes Meyer-Brandis, whose work investigates the intersection of human and animal existence in ecological contexts, reflect the same spirit of engagement with the environment that defined Arte Povera.

Arte Povera’s insistence on using “poor” materials as a statement against consumerism and excess has found a renewed relevance in the digital age, where wastefulness and environmental degradation are ever-present concerns. By returning to raw, organic, and locally sourced materials, many contemporary eco-artists are using the same principles as Arte Povera to critique the unsustainable practices of modern industrial society. The movement’s influence in this regard has had a lasting impact on the ways in which art can serve as a vehicle for social and environmental change.

12. Conclusion

Arte Povera, emerging in Italy during the late 1960s, remains a pivotal movement in contemporary art. Rooted in the socio-political turbulence of post-war Italy, the movement sought to break away from traditional artistic forms, challenging both the art world and societal norms. Through its focus on “poor” materials—discarded objects, natural elements, and found objects Arte Povera not only rejected the commercialized art market but also embraced the tactile and transformative power of art, encouraging a new engagement between the artwork and the viewer.

At the heart of Arte Povera lies a deep philosophical exploration of existence, authenticity, and materiality. The movement’s engagement with phenomenology and existentialist ideas, especially the works of artists such as Michelangelo Pistoletto, Giuseppe Penone, and Mario Merz, emphasized the materiality of the world as an essential aspect of understanding human existence. Arte Povera’s search for authenticity was not just in terms of artistic production but also in reflecting the authenticity of human experience in an ever-changing and industrialized world.

Despite its relatively short duration, the influence of Arte Povera extended far beyond its origins in Italy, impacting international art movements and laying the groundwork for environmental art and conceptual art. The movement’s emphasis on interaction, process, and the physicality of materials has made a lasting impact on contemporary art, particularly in today’s digital era. Arte Povera’s relevance continues to resonate, as its core themes of anti-consumerism, materiality, and environmental consciousness remain highly pertinent.

Looking forward, the enduring legacy of Arte Povera invites new generations of artists and thinkers to reflect on the role of art in addressing contemporary concerns about sustainability, authenticity, and the environment. The movement’s principles of rejecting consumerism and embracing impermanence offer a counterpoint to the digitization of contemporary culture and serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of physicality, materiality, and human connection in the arts.

In conclusion, Arte Povera’s radical embrace of impermanent, humble materials and its philosophical engagement with existentialist ideas have secured its place as a significant movement in art history. Its continued relevance and influence in contemporary art attest to the enduring power of art to provoke thought, challenge norms, and inspire new ways of seeing and understanding the world.